Deeply Distressed Places in the Midwest

A county level analysis of agglomerations, quality of life and human capital

One important role of research on place-based policies lies in identifying locations that are face deep economic distress. The goal of this is to consider what policies — federal, state, regional or local — that might improve economic outcomes for businesses and households in these places.

The approach I use here is to blend two existing study approaches that consider the role of agglomerations and human capital along with quality of life. I do so because these are the dominant explanations for the location decisions of businesses and households. Places that under perform in both agglomerations and quality of life face special challenges to economic and population growth.

I begin with agglomerations.

Agglomerations may result from advantageous physical geography, such as the presence of safe harbor or seaport, waterways and later rail or road access. They may occur due to high transportation costs of inputs pushing commerce to locate nearby.

The persistence of natural advantages, resulting in investment or infrastructure development may extend agglomerations long after the original purposes were no longer meaningful to trade. New York, Boston, London and Paris are no longer highly productive because of their excellent seaports and connecting rivers. Rather, the history of development advantaged those places for later agglomerations that relied on knowledge.

The first popular economic description of agglomerations is attributable to Alfred Marshall. He noted that people doing similar tasks cluster together and generate ‘knowledge spillovers.” He famously noted that “people following the same skilled trade get from near neighborhood to one another” so that “the mysteries of the trade become no mysteries” as information is transmitted “in the air.”1

An important contribution to the agglomerations literature was offered by Ed Glaeser and Matthew Resseger which examined the complementarity of cities and skills (education). The hypothesis they tested was whether or not agglomerations were more attributable to knowledge spillovers or other explanations (infrastructure, supply chains, etc.)

The study was nice for many reasons (I linked a free version above). The heart of the analysis had two pieces. One was a micro analysis of 2 million plus workers in several models of human capital (a form of a Mincerian wage model with education and job tenure), that included levels of educational attainment within the city they lived.

The first set of findings from their study of individual workers in urban settings was that skills and experience mattered more in more urban places, suggesting a role of education in agglomerations. But, bolstering a set of fewer, MSA level regressions, they find that these benefits only really occur in cities with higher than average levels of education. This is an interesting finding, that doesn’t fully reject alternative interpretations.

A second approach examined the role of infrastructure spending and found little evidence that capital investment was played a role in the higher wages and productivity predicted by agglomerations. However, this empirical test was limited by data and technical issues, that remain today.

A third portion of the analysis confirmed higher wages for equivalently educated workers in urban places, that also rise faster as workers stay on the job. This produced two additional findings that imply the existence of agglomerations (workers are more productive in urban places). The second finding implies that part of the gains are due to knowledge spillovers connected to faster learning, a finding that Glaeser and David Maré had reported in an earlier paper.

All of this is interesting, but it focuses solely on metropolitan areas. The data on individuals is not available at the county level, offering only ‘rural’ designation for each state. However, to set up the issue, Glaeser and Resseger ran a simple agglomerations model where output per worker is a function of the size of the city.

log(Y/N) = log(A) + bLog(Population) + e Equation 1

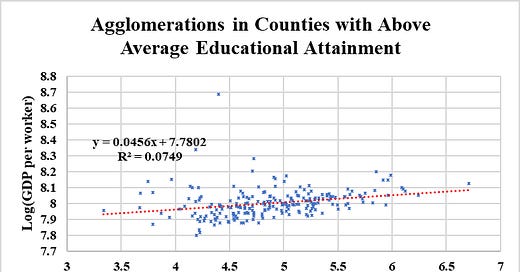

They first ran this model on the entire sample of cities, then on two separate samples, splitting cities into the top and bottom half of educational attainment (share of adults with a BA or higher degree).

Doing so revealed pretty strong evidence of agglomerations (higher Y/N in bigger places) in the well-educated cities, but none in the cities with the lower half of the educational attainment. This approach is a good way to discern which counties might not enjoy the benefits of agglomerations, a likely source of distress. But, education and agglomerations aren’t everything, as any reader of this blog will appreciate. There is also quality of life.

My colleagues Amanda Weinstein, Emily Wornell and I have been working on ways to measure quality of life and its effect on the economy. we use the well-known Rosen-Roback approach, which offers an intuitive way to measure the bundle of unobserved amenities that appear in any community.

I’ve written about it in this blog, and with Brookings Metro, which are derived from our academic paper. Let me summarize it briefly for our purposes here.

We don’t know what people like, but we do know that families will pay more for a home in a location they prefer. So, if we can use a statistical model of the price of a home, using home characteristics, like number of rooms, size, construction type, age, etc. we can do a good job predicting the price of a home. The portion of the home that we cannot fully explain is due to unobserved effects in that community.

If the unobserved effect has a positive value, that means the characteristics of the home ‘under predict’ its value. So, that home must be located in a place with unobservable amenities that people in that community — and importantly outside that community value.

If the unobserved effect has a negative value, that means the characteristics of the home ‘over predict’ the value of that home. So, that house is located in a place with a less desirable set of amenities.

Economists spend a lot of time estimating these models, with the hopes of very carefully measuring things like the negative effect of airport noise, school quality, types of natural amenities, the proximity of registered sex offenders, access to public transport, and Superfund sites.

These studies can tell us how much to spend on each of these. For example, having a good local school can improve home values by 30% or more, so we are probably way underinvesting in public education. But, they don’t perform well in measuring overall quality of life, just important slices of it.

Our approach, which we do at the county level gives us the housing market measure of a community’s bundle of amenities, not just a single one. But of course, that is only halve the story. Labor markets also matter.

So, following the Rosen-Roback approach, we do a similar hedonic/Mincerian wage function at the county level. Here, we predict wages as a function of education, age, industry structure and demographics. A portion of wages are unexplained for each county, either a positive or negative value.

The interpretation of this unexplained wage value is similar to the unexplained home value. The difference is that people would be willing to forego some wages to live in a place they prefer and demand more wages for a place they dislike.

So, to live in a nice place (whatever that is) people are willing to pay more for a home and give up some salary. To live in a place they dislike, they will be willing to pay les for a home but demand a higher salary. Pretty straightforward stuff from economics almost a half century ago.

We put all of this together because for a place to thrive, it really needs to have some overriding economic reason for success. That could come from quality of life (which is a strong predictor of population and employment growth) or it could come from agglomerations, which give workers and businesses higher returns (in the form of wages and worker productivity).

To then define distressed counties in the Midwest (IL, IN, MI, OH, WI), I used county level data on GDP, employment and population to estimate the equation 1 above. I use 2022 data, except for education which is the 5 year American Community Survey average.

As Glaeser and Resseger did, I also separated these counties into two equal groups, based on the share of their adults with a bachelor’s degree or higher. This is a common way to distinguish human capital, despite its imperfections.

In the better educated half of counties, we observe an elasticity of agglomeration of 4.5%. This means increasing county size by 10% would increase worker productivity by just under half a percent (0.45%).

However, in the counties with below average levels of educational attainment there was no evidence of agglomerations. These results are very similar to the reported findings in Glaeser and Resseger (except that I use county, not metropolitan data, so my elasticity of agglomeration is a bit smaller).

This provides us a first good measure of distressed places. Those locations, with below average levels of educational attainment, but also have lower than expected levels of agglomeration. These are places where size offers no economic advantage due to low levels of education among the population.

Of course, not everyone likes to live in urban places, and particularly smaller rural places may be attractive to many. So, especially in the post-COVID period, we might expect more population growth in high quality of life places as a consequence of the availability of remote work. I wrote a bit about that here.

So, it is natural that we would exclude places with positive measures of quality of life from a list of distressed counties. So, that leaves us with a simple measure of distress; lower than average levels of education, below expected levels of agglomerations and low quality of life.

Of the 438 counties in these five Great Lakes - Midwest states, 41 make the distressed county list. They are mapped below.

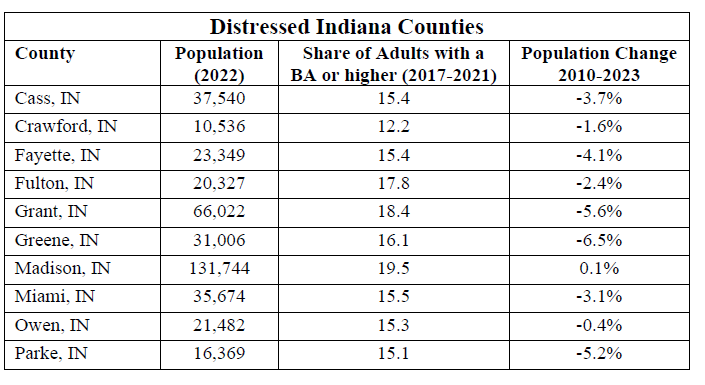

These counties are small, averaging just over 30,000 residents. The average county has just under 17 percent of adults with a bachelor’s degree or higher, which is less than half the national average. Most interestingly, all but four of these counties have lost population since 2010.

Michigan, Illinois and Indiana fare poorly in this measure, while Wisconsin and Ohio have only a single county each in the distressed category. The following tables illustrate each state’s distressed counties.

Other than a bit of geographic clustering in north central Indiana and the upper peninsula of Michigan, there’s little clear pattern here. The exception to that is the interesting question of the low distress representation in Wisconsin and Ohio. This may be due to more decentralized fiscal decision making in these states.

Michigan, Illinois and Indiana are highly centralized tax and spending states. This might have permitted the Wisconsin and Ohio counties to make better, or at least more expeditious quality of life investments. That is an interesting opportunity for future research.

Over the past couple decades, very convincing research points to ‘knowledge spillovers’ as the primary cause of agglomerations. More simply, cities are good places to work and start a business, because there your access to smart people provides a substantial productivity boost.

Cities that have below average levels of education get no such boost of productivity. For these places, the presence of a city offers only costs, without benefits to worker productivity.

Research in this same strain points to quality of life as a magnet for people. So, urban or rural places that lack the productivity boosting benefits of education and agglomeration might still benefit from a rich set of amenities. The most important of these are good schools, low crime rates, followed by some access to natural amenities and ‘endogenous’ amenities that follow population growth.

Places with agglomeration benefits and quality of life should expect to grow, with high levels of these attributes acting as a centripetal force towards a city or county. Conversely, places with no agglomeration benefits and low quality of life will act not as an attractor of people, but as a centrifugal force, moving people away.

This measure of distress in Great Lakes states performs well in these measures, though in a region where most counties are losing people, we hardly identified all of them as in distress. What is clear is that these places are at special risk over the coming years of the 21st century. They lack both amenities and the productivity boost of agglomerations that are the central force driving population and employment growth.

These are places where place-based policies are especially critical to help reverse decline and boost the economic prospects of residents. Without such policies, including restructuring of fiscal centralization to allow more locally driven investment, it seems likely that all but a handful of these 41 counties will continue to see population decline and economic stagnation for decades to come.

Marshall, A. (1920). Principles of economics (8th ed). Macmillan.

Micheal one commentator on public TV said that one of the reasons Trump was elected was that the democrats were seen as elitist because they put so much emphasis on higher education! Somehow we have to make it sound as though it in the benefit of all no matter what profession or vocation they choose and find a way to make it within their reach. Having the legislature decrease the portion that they pay certainly doesn’t help and is short sighted! JR

This comes close to an issue I've been wondering about. Is it possible that the growth in the use of non-disclosure agreements and employee non-compete agreements might reduce the rate of economic growth attributed to education?