In 2020, the Manhattan Institute published the Cost of Thriving Index (COTI). What followed was broad and substantive criticism from folks like Matthew Yglesias at Vox, Mark Perry at the American Enterprise Institute, Michael Strain at AEI, Robert Verbruggen at National Review, Oliver Sherouse on his blog, and on lengthy twitter threads by Scott Winship.

Normally, this enormity of detailed, technically rigorous, and and conceptually clear criticism would cause an endeavor of this sort to quietly disappear. That would’ve been the most productive outcome for the COTI. But, the 2023 version of the Cost of Thriving Index has migrated to the growing library of bad ideas known as The American Compass.

The original COTI argued that it has become so costly for middle class families to earn a decent income that they can no longer do so. Many will no doubt find this view appealing, but is it at all true? The COTI itself offers some insight into the measurement problem, and frankly the lack of seriousness of the author. The COTI makes three claims of the problem of current measurements of the standard of living, that economists use. From the 2020 version, Oren Cass writes that current measures of inflation hold three problems.

Quality Adjustment. Products and services that rise substantially in price but in proportion to measured quality improvements can become unaffordable, while having no effect on inflation.

Risk-Sharing. New products and services can increase costs for the entire population yet deliver benefits to only a very small share, while having no effect on inflation.

Social Norms. Society-wide changes in behaviors and expectations can alter the value or necessity of a good or service, while having no effect on inflation.

At first blush, these might seem harmless little assertions. But, Cass constructed the COTI to overturn the otherwise accepted fact that people are now better off than they were several decades ago. The absolute best work on that issue is the book Superabundance, whose title belies its deeply serious analysis.

The premise of COTI is wrong, and represents yet another stab at crafting a post-conservative economic policy agenda for populist politicians. Coming from Mitt Romney’s former policy advisor, this is sweet indeed. The studies I cited above outlined individual weaknesses in COTI and in some instances dealt the entirety of the work a fatal blow. But, it is back. So, in this post, I offer three points that are intended to put COTI behind us. I’ll fall short in that endeavor, bad ideas are too persistent. But, here goes.

On the first point, I confess a bit of confusion on the “quality adjustment” description. In Cass’ full report, he seems to note that many products are ‘lumpy’ and that discrete price changes in goods are so large as to prevent families from consuming them. For example, he argues that if a family wished to purchase the healthcare available in the 1970’s, no provider would be willing to do so, or provide them comparable care (pg 12). But, that is nonsensical.

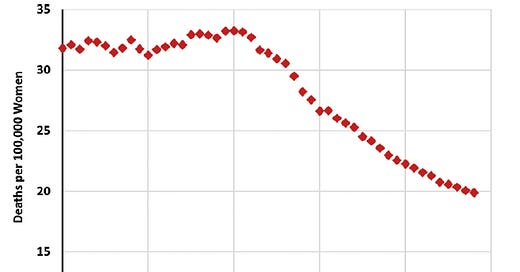

Much of the aggregate cost of healthcare growth in the USA is attributable to procedures and treatments unavailable in the 1970’s. If you developed breast cancer in say, 1985, you died at a much higher rate, as this graph from Hendrick, et. al., 2021 illustrates.

Traditional price indices such as the Consumer Price Index or Personal Consumption Price Index measure quality adjustments imperfectly. But, Cass seems to argue that no only should we ignore quality adjustments in a price index, we should view a consumers inability to not receive this type of medical care as evidence that the standard of living has declined. That idea is so absurd that it cannot even be labeled as ‘flawed.’

But, there’s an easy way to illustrate this without undertaking extensive value of life estimates or an econometric hedonic valuation of quality change. Let us just challenge his calculations on the transportation index.

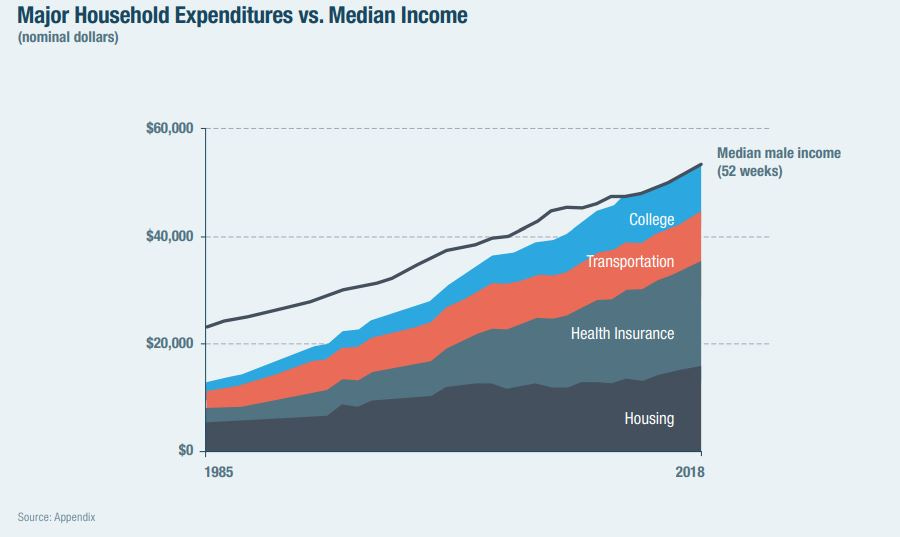

In this figure, Cass introduces the notion, that wages have not kept up with the cost of living (here defined as being the sole breadwinner in a family). And, as one can see, the cost of transportation is growing over time.

The method behind this estimate seems straightforward. Choose annual mileage (15,000), and use the Bureau of Transportation Statistics on cost of usage (both fixed and variable costs). The BTS method he uses calculates a 5 year ownership of an automobile throughout the observed period, using data and analysis from the AAA.

This would seem to be a good approach to prices. But, it ignores quality improvements. Deaths per vehicle mile travelled (VMT) alone have more than halved since 1985.

Source: Bureau of Transportation Statistics

Again, Mr. Cass not only thinks that this should be ignored in a cost of living data. He also argues that being forced to pay for quality improvements one does not want is evidence of a lower standard of living today. This is a bizarre argument, that he employs again and again in the conceptualization of the COTI.

Admittedly, I view these questions through the prism of an economist. That means choice itself has value, so that part of his argument may possess some salience. However, not dying in an automobile has value. Economists assume households recognize and make consumption decisions based on both these factors (and study our own assumptions).

The fact that markets move away from vehicles may partially reflect regulatory intervention, but it also surely reflect household preferences. That a market for less safe, new cars no longer exists is not primarily due to non-market forces. If it were, the Yugo would’ve been a huge success. Rather, it is an expression of preferences that should naturally be included in a price index. Though, for Mr. Cass, I’ll just note that this natty auto remains available on Autotrader.

However, my criticisms of the COTI aren’t merely conceptual. Mr. Cass makes some fundamental empirical errors. By comparing prices across time, without accounting for any change in consumer preferences or quality, he necessarily errs. For example if you don’t consider that your chance of dying in an automobile is less than half what it was in 1985, making an index called the Cost of Thriving Index just won’t measure what you think it does.

A better way to make this comparison might be to eschew entirely the use of price indices. I did so in my recent article, The Time Price of Education. In this, I use a method developed by William Baumol of estimating the ‘time price’ of an object. This measure simply converts earnings into hours worked to buy a particular item.

I use the usual weekly wages by full time workers, of all type, second quartile. For hours worked, I use the average annual hours worked by manufacturing employees. These choices are designed to capture a middle class, full time employed worker, but choosing a different wage recipient or some other measure of hours worked (all would include part time workers), has no meaningful effect on the results.

This calculation changes the price of an item, with the hours of work it requires from our representative worker to acquire the item. In a comparative calculation, I make one very simple adjustment for quality. Instead of using the 5 year estimate of auto survival that is employed by the AAA, I use the actual automobile longevity estimate from the Bureau of Transportation Statistics.

This is not a perfect calculation, since the AAA methodology includes payments, maintenance and insurance as a fixed cost. So, in the early years of individual ownership, this is a low estimate, but in the longer term it is a much higher estimate of costs. When one stops paying for a car, the fixed costs plummet. Since the mean is moving substantially, from 7.2 years in 1983 to over 12 last year, these differences likely net out. But, this is a good thesis project for an undergraduate. I used the 5 year estimate from 1985, adjusting it linearly to the 1995 level, which was the first year of annual data.

The Time Price estimate, adjusted for the durability of an automobile reflects a very different story than that told by Mr. Cass in his COTI estimate. In terms of the actual amount of time a worker must spend laboring to pay for the use and operation of a vehicle, the costs were 51.6 percent lower in 2022 than they were in 1985.

The use of the AAA estimate is helpful, particularly in that it includes the variability of commodity prices (fuel). However, the AAA calculation, and that of Mr. Cass, uses a single representative vehicle, with lower fuel efficiency than the fleet. That is a small matter in the calculation in any given year, particularly since the durability of automobiles is now so long. However, the accumulated effect may be substantial.

Importantly, there’s no calculation for safety improvements in either of these estimates. I didn’t do it, just for ease of computation, but it is not conceptually a hard matter. If one’s lifetime risk of death in an automobile accident declined from roughly 1:50 to 1:101 since 1985, using a value of life estimate deployed by the Department of Transportation, the value of that risk reduction is roughly $89,000. That is roughly $2,400 per year a consumer should be willing to pay to reduce risk of death in an automobile.

That estimate represents roughly 22 percent of the annual cost of ownership. Had I included that in my calculation, it would have reduced the Time Price of a fixed quality unit of transportation from 271 hours to 212 hours in 2022. Thus, adjusting for the declining risk of death, as a quality adjustment would reduce the Time Price of transportation by 49 percent from 1985 to 2022.

The many authors outlined above noted that Mr. Cass offered profoundly flawed analysis in his COTI. In addition to that, I am making a further point. I is not that Mr. Cass mis-values quality improvements, or has employed a biased Bayesian estimator in these calculations. From the very beginning, his conceptualization of the COTI as telling us something meaningful about standards of living (or thriving) is addled. There’s no more charitable word for it.

The second aim of COTI is to suggest that ‘risk-sharing’ distorts measurement of benefits of new products, because as Mr. Cass says “new products and services can increase costs for the entire population yet deliver benefits to only a very small share, while having no effect on inflation.”

What I think he’s trying to say here is that something like one’s employer based health insurance includes, well risk sharing. Insurance itself is a financing tool that shares risk. Households buy health insurance so that in the case of say, malignant lung cancer, medical costs can be paid with reducing one’s family to penury.

This is not a difficult concept to understand. Indeed, there’s a significant body of research on risk sharing behavior among primates. Apparently Bonobo monkeys engage in it. Health, life, auto or home insurance all reflects a durable mechanism for risk-sharing. The is pretty uncontroversial, but Mr. Cass seems to argue that as new, improved medical procedures are added to the portfolio of a covered health plan, that the growing costs are not covered by inflationary measures, such as the CPI or PCE.

He is wrong, in the first sense in that these additional costs reflect quality improvements. I suspect a health plan purchased in 1985 that offered a fixed technology, fixed treatment promise would today be quite inexpensive. In that plan, a subscriber who bought health insurance in 1985 would presumably not pay for, nor receive any new therapies. So, if you developed lung cancer in 2025, you got only the 1985 treatment.

We cannot know this of course, because no such plans exist (or at least none of which I am aware). Perhaps Lloyd’s of London might write such an individualized plan. But, the absence of such a plan is likely because there is no demand for it. And that brings us to the second critique of the issue.

In judging the consumption of services, including health or financing, we cannot just ignore quality changes. One must do the math, whether this is something concrete like gas mileage or something more opaque, such the inclusion of low probability treatments in health insurance costs.

Absent the ability or willingness to measure quality adjustments, one can still derive inference from human behavior. Economics has a modest point to make on this that bears on the healthcare share of spending in Mr. Cass Cost of Thriving Index.

If the inclusion of ‘unwanted’ procedures in health insurance leads to consumers buying less insurance or healthcare, we might conclude the quality improvements are not worth the extra expenditures. These might be considered goods that as we become richer, we spend a declining share of our income on them. Many products fall into this category. We call these ‘normal goods.’

Alternatively, if we value a good more as we grow in affluence, we would call that a ‘luxury good.’ We would then spending an increasing share of our income on them as we become richer. This should be a pretty uncontroversial definition, since we’ve been using it since about 1890.

In Mr. Cass’s context, that means we could bring more than a century of economic theory to bear on his problem. He suggests that the quality improvements that boost the price of health insurance (for example) make things more expensive. These aren’t captured by traditional measures of inflation, and thus make it harder for Americans to thrive.

However, his own data tell a different story. Indeed, according to Mr. Cass’ own calculations, the health insurance spending of which he complains is actually a ‘luxury good’.

Americans aren’t spending 35.4% of their earnings on healthcare. It hasn’t grown 3.5 times over the past four decades as a share of our earnings. But, that is what Mr. Cass claims in COTI. There are many problems in healthcare, as I have chronicled in several places, including this platform. However, medical innovation is not among them, and the value households place on newer therapies is significant.

Maybe the easiest way to illustrate the folly of Mr. Cass’ argument is simply to take it to its full conclusion. Let me see if a logical narrative helps.

“The cost of risk-sharing arrangements like health or homeowner insurance is poorly measured by inflation. This is because this risk-sharing arrangement means consumers are paying for some services they don’t get. That means the median insurance purchaser is unable to thrive. However, if they did contract the rare disease, then they could be viewed as thriving.”

Hopefully, this sounds bizarre to you. Logic should be enough to insulate you from badness that is COTI. But, we haven’t got to the best part yet. The third major flawed observation of COTI is: “Society-wide changes in behaviors and expectations can alter the value or necessity of a good or service, while having no effect on inflation.”

This is true. I believe that it can be treated as axiomatic the the social expectation that I wear trousers to the class I teach in no way affects the aggregate price level. As funny as this sounds, I don’t believe that’s quite what Mr. Cass means. If it is, we are in total agreement. What I think he argues that this modern world asks us to live beyond our means, buying things we do not wish, and that prevents the modern man from thriving.

This is not a novel observation. The following extract comes from Kate Gannett Wells, writing in The North American Review in 1891.

I think this is the essence of Mr. Cass’ argument. She admirably lays out most of his argument here, taking it to its logical conclusion.

Ms. Wells was a leader in the anti-suffragist movement. In her defense, some suggest that this seems to have been primarily on the grounds that non-public activity was so important that half the population should attend to it. She evidently did not feel bound to that notion herself. Nonetheless, she has done something important for posterity. She’s given us a succinct insight into the reasoning that motivates the Cost of Thriving Index. (this is from page 123-124).

Here I think is the point of the Cost of Living Index. Mr. Cass recognizes, as did Ms. Wells, that consumption differences of fashion “constitute the difference in cost between past and present.”

A better writer than either myself or Mr. Cass could drum up an argument here. I am partial to C.S. Lewis on the matter, and suggest this post from The Imaginative Conservative. In it, he cites Lewis, describing nostalgia as “the inconsolable longing in the heart for we know not what.”

In a nutshell, that is the entirety of Mr. Cass’ work in Cost of Thriving Index and more broadly in the policies he is trying to formulate in American Compass. The formulation of the economic argument in the COTI, and in much of the rest of the work published in American Compass is that. An inconsolable longing in the heart for we know not what.

George Will offered a fairly clear criticism of what this movement has morphed into; Making America great by making it 1953 again. Oren Cass is less ambitious than Mr. Trump. With the COTI he looks back only to 1985.

It is with some irony that 1985 fell between the last two consecutive elections in which the GOP won a majority of the popular vote. As a purely political matter, the fictional claim that Americans are worse off than they were in 1985 may be popular. Indeed, in the 2023 version of the COTI, Mr. Cass attempts to cast aside the many objections of economists, by offering a survey suggesting many Americans agree with his findings.

In his defense, Mr. Cass has done as much as anyone in crafting a populist GOP economic platform from the tempête de merde of the past few years. He has worked tirelessly to create something from the nothingness. Still, his Cost of Living Index is a deeply unserious attempt at analyzing the problem. It would be far more economical to simply make a claim without evidence. The constituency for economic populism is fully acculturated to that approach.

First, leave the finest of Lee Iacocca’s K-cars out of this!

Second, your point on transportation is well taken. A 1992 Camry had a MSRP of $20,000, with many paying well above because of demand. A 2023 Camry - bigger, safer with far more airbags, more efficient, faster, and with entertainment and technologies like stability control requiring immense computing power and sensors and pre-collision braking, has a MSRP of $25,000. Like the 1992 Camry is today, many will be in daily service in 2053. Hard to see how a Camry consumer is worse off today than in 1992.

Third, how does he account for many middle class who bought a house in the last 10 years and are enjoying a sub 3% mortgage while benefiting from house price appreciation (same with any owned vehicle)?