My latest column again challenges the outrageous and growing malevolency of Indiana’s hospital monopolies. In this piece, I reproduce that work, and provide the data and data sources.

I begin by noting that not-for-profit firms file an IRS 990, which is a public document. The folks at ProPublica collect and make these available online. This is a marvelous public service.

At issue in much of this is the term profits. To summarize, the IRS requires reporting of net profits, and requires the reporting of “charity care” at actual cost, not the price the hospital would’ve charged to insured patients. So, hospital NFP’s report this to the IRS, but when they report their costs to the state, they report a different value (presumably what they would have charged to insured patients). There is an abundant economic literature on the profit and cost issue for regulated firms and monopolists, which I won’t discuss. Just google ‘managerial emoluments’ to see the breadth of studies that explain marble entranceways in these firms. I mean, if you are going to get criticized for profits, why not have marble entranceways, mahogany desks, etc. and call it costs . . .

Corporations make operating profits and turn some share of that back into expanding operations for later years (R&D, new capital expenses, etc.) and return some of it to stockholders. NFP firms don’t do that, which is how IU HEalth accrued some $9 Billion as reported in the links above.

Here’s the column with data and links:

Last month the state’s largest healthcare firm, IU Health, announced it would freeze prices through 2025. That end date is tentative, and the plan is short on public details. However, there has been enough reporting about the issue that we can begin to understand how financially important this is for businesses and consumers. It is also useful to interpret this decision in light of the overall hospital monopoly problem in Indiana.

IU Health has claimed that this price freeze will save Hoosiers about $1 billion over the five-year freeze from 2021 through 2025. This may be correct, but this not-for-profit hospital system earned $1.2 billion in profits in 2020. Numbers of this size seem almost abstract and difficult to assess without more context. By comparison, IU Health’s profit rate is four times higher than what Walmart has posted in any of the 52 years it is been a corporation. Last year, IU Health reported profits of more than $33,000 per employee. (Note: the longer history is available in my book on Walmart, page 155. Divide $1.2 billion by their employment).

IU Health has been able to sustain what economists term supra-normal profits for many years because it has become a strong regional monopoly in many parts of the state. This allows the firm to price its medical services at more than three times the federal reimbursement level. This is high by national standards, but to be fair to IU Health, it isn’t even the worst in Indiana on some measures. (Note: this comes from a Rand study, which has been through several iterations, and is growing in its quality and breadth. You can download the data, a book and play with a nice online map on their site.)

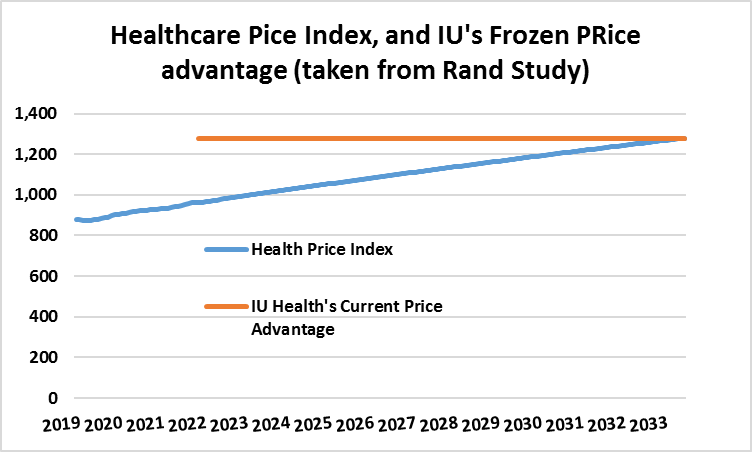

IU Health claims that it can achieve national parity on prices in three to seven years. My arithmetic suggests it’ll take more than a dozen years of price freezes to get back to national averages. But, IU Health could freeze its prices for another 40 years before it got close to exhausting its $9 billion in accrued profits.

Note: This graphic displays the current health price index rising at its 36 month average =(Nov 2018-Nov 2021) through convergence with IU’s current advantage. That is about 12 years, 5 months of a price freeze.

To put the scale of IU Health’s monopoly in context requires digesting some shocking facts. This sprawling firm could give away all its healthcare services for free through all of 2022, pay all its bills and employees and would still finish the year with more savings than the entire State of Indiana’s Rainy Day Fund, which is now at record levels. (Note: The ‘no fee’ option is simply its accrued profits, minus its 2020 operating expense, compared to Indiana’s current budget excess in Rainy Day and similar reserve funds.)

The simple truth is that the IU Health price freeze is a public relations gimmick that will have no noticeable effect on the lives or finances of Hoosiers. But, the notion that IU Health would spend $1 billion over five years on a public relations gimmick illustrates the deep legal and legislative challenges it anticipates. The firm is right to be worried.

Indiana is among the very worst places for healthcare spending in the nation. In 2019, I authored a couple of studies that caused the hospital lobby to target me with remarkable vigor. Both the lobbyist from the Indiana Hospital Association and the local IU Health CEO wrote Op-Ed columns accusing me of deceit. They pressured my university leadership to silence me and hired consultants to prove me wrong. The hospital association lobbyist even made the repugnant claim that these high prices are caused entirely by the poor health of Hoosiers.

The problem for Indiana’s hospitals is that I was right. In fact, I wasn’t even the first economist to identify the problem, nor am I the most recent. There are literally dozens of studies from well-respected think tanks and university professors documenting the monopoly pricing problem in Indiana. Ironically, the consultants hired by the hospital association reported levels of market power in Indiana that are everywhere above the threshold set by the U.S. Department of Justice.

Note: the Department of Justice publishes Merger Guidelines that describe the level of market concentration at which the DOJ would intervene. There are hundreds of measures of market power, but the DOJ lists the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index as preferred (HHI). At post merger HHI < 1,000 they will typically regard this as unconcentrated. Between 1,0000 and 1,800 they will typically allow small mergers, that increase HHI by less than 100. Mergers that result in post merger HHI of greater than 1,800, particularly if they increase the HHI by 50 points or more, will be opposed unless there are some mitigating factors. These HHI shown NERA didn’t differentiate between ownership (an odd, and economically unsupportable argument). So, they treat the Muncie ACA region as having three competing hospitals. That would be crushed in court.

You don’t need a lot of economic theory and statistical models to understand the problem. The price freeze gimmick is a tacit admission of the pricing problem many economists identified in Indiana. Even more convincingly, we have actual price data with which to compare hospitals, and the East Central Indiana hospital monopoly is ground zero for these shenanigans.

East Central Indiana’s federally designated healthcare market is a textbook monopoly. There are three hospitals in the region, each owned by IU Health. Since the Indiana legislature pressured hospitals to report prices into a public database, we can make clear comparisons about their monopolistic pricing practices. In the Muncie and the surrounding counties, normal childbirth costs between $19,488 and $21,305. In nearby Anderson, where three hospitals compete for business, normal childbirth costs between $2,671 and $7,380.

(Note: This tool doesn’t use ACA definitions of healthcare markets, but instead uses much broader geographies than the Fed’s. Neither is perfect, but the Fed definition is designed to capture geographic markets, while the IHA tool is designed with something altogether different in mind).

This is profoundly hurtful to local businesses and consumers. From 2010 to 2019, Muncie and Delaware County’s total Gross Domestic Product grew by an accumulated $914 million. But, over those same years, the accrued profit by IU Health Ball Memorial Hospital alone was $596 million. That’s right, profits to this local not-for-profit hospital swallowed 65.2 percent of all the economic growth in Muncie and Delaware County from 2010 to 2019.

More shockingly, the total cost of providing this healthcare over this time only grew by only $118 million. Profits grew at nearly five times of the cost of healthcare in Muncie from 2010 to 2018. Again, these are the data the hospital reports to the Internal Revenue Service. They tend to use other data in their public relations and Op-Ed columns. I will leave it to the reader which data to believe.

In an Op-Ed column in 2019, the IU Health Ball Memorial CEO claimed that his hospital was "supporting the community’s vitality." I don’t think "support" is quite the word I’d choose to describe what the hospital monopoly is doing to the region, but this newspaper has editorial standards.

None of this was necessary. Had Indiana enforced anti-trust laws using federal guidelines, almost no hospital acquisition would have occurred over the past quarter century. But it gets worse — once the not-for-profit hospital system created its networks, it began to solidify its power and set prices like old school monopolists. It bought physicians practices just like a monopolist seeking to control the upstream markets. It bought affiliated health providers so it can control the downstream market.

Indiana’s hospitals systems are the modern equivalent of gilded-age robber barons. One exquisite example is that in early 2020, during the midst of legislative hearings on hospital monopolies, the highest-priced hospital system in the state took its entire board of directors to the Naples, Florida Ritz-Carlton for a board retreat, where room prices there begin at $1,200 a night.

(Note: There are a large number of hospital employees who know about the abuses all too well. This is some inside information, and I didn’t get it by email, so IHA, don’t bother with another Open Records request to hunt down that employee).

Congress, the Department of Justice and the Indiana legislature will surely continue to tighten the oversight of hospitals, but their real fear is civil litigation. There are 6.5 million individual plaintiffs in Indiana and another 250,000 employers who provide health insurance. There are also thousands of frustrated physicians, nurses and other healthcare workers who see the effect of this monopoly on patients and communities. The current pandemic required personal sacrifice, heroism and exhausting work schedules for these workers. For their not-for-profit employers, it was the profit opportunity of a lifetime.

Note: This column was updated on 1/10/22 at 12:15 P.M. to fix two typos found by readers. Thank you.