What is behind the shocking decline in college enrollment in Indiana?

A summary of my November 3, 2022 talk at University of Indianapolis

On November 3, 2022, I participated in the Insight Series at the University of Indianapolis’ Center of Excellence in Leadership and Learning. The focus was on the decline in college enrollment in Indiana. This is an extension of those remarks.

I begin by noting that differences in economic growth across regions (nations, states, cities and counties) is almost exclusively caused by differences in educational attainment. Poorly educated places are poor and grow slowly, while well educated places are prosperous and grow more quickly.

Indiana ranks 44th in the share of adults with a bachelor’s degree, and 38th for those with a BA/BS or higher. This explains why our incomes are lower than the national average. It also explains why our incomes are growing more slowly than the nation as a whole. This is worsening, which will cause us to diverge from our neighbors across the country.

Since 2015, our college going rate has declined by 13 percent. This marks roughly 5,000 fewer Hoosier kids heading to college each year, from a cohort of roughly 80,000, which has grown by roughly 5,200 over the same time period. This decline is roughly twice the national average. There’s no way to put a happy face on it, Indiana’s educational attainment is reversing, and the negative shock to on prosperity will continue to be felt for several decades.

The question of importance, is why is this happening? I think there are five competing hypotheses about the decline in Hoosier kids heading to college. They are:

•Decline in benefits of a post-secondary education?

•Reduced perception about benefits of a post-secondary education?

•Colleges are too “Woke” or indoctrination hubs?

•Tuition cost of secondary education is increasing?

•Available student aid is declining (declining state support affects net price)?

One way to examine these is to try to reject each of these hypotheses, in turn. If we cannot, I think that is at least a rough and ready way to further consider the issue.

One caveat is that I’m writing about trends, not the cyclical nature of college attendance. COVID-19 shocked enrollment nationwide by 2-3 percent, which has mostly rebounded. Also, the increase in nominal wages for unskilled work likely incentivized many to delay school. These short term shocks aren’t at issue, and we should expect an increase in the college going rate next year. That welcome news won’t be sufficient to cause us to get out of the declining trend.

So, has there been a decline in the benefits of a post-secondary education that would warrant students substituting work for college? The short answer is no. This year of help wanted ads makes pretty clear the stable differential between the mean starting salary by educational attainment in these help wanted advertisements

Source: Real Time Intelligence (reported by Chmura Economics, Center for Business and Economic Research

But, much of the benefits of college lie in employment stability, not just wage. So, if we calculate the higher labor force participation rate, times the wage premium, we get an expected wage premium over high school.

This wage premium almost perfectly illustrates the “treatment effect” education has on employability and wages. Each year of education after age 16 increases wages by about 15%. This is good evidence that the learning, not the sheepskin or signaling effect is driving the economic benefits of college. Note, these are help wanted ads in Indiana, with the labor force participation rate differences inferred from national data.

Still, the biggest reason one might consider going to college is because that’s where future job growth is clustered. This graphic depicts the cumulative employment growth by educational attainment level in the USA for the past three decades. This is for workers aged 25 and older.

Source: Current Population Survey, reported by Federal Reserve Economic Data (workers aged 24 and higher)

Of course, there are a few who argue that this is due to credential inflation. It is not an unreasonable hypothesis that employers would use a diploma as a screening device for new workers, even in occupations that don’t require a degree. That’s effectively what Richard Vedder and Bryan Caplan have argued. Among the many pieces of evidence that they are mistaken is simply that for credential inflation to occur, we would expect real wages to grow more slowly (or actually decline) among those with more education. However, real wage growth among better educated workers outpaces those of less educated workers throughout this time period.

The fact is that if you wish to be in an occupation with increasing demand, it requires post-secondary education, and mostly a 4-year college degree or higher. There is just no evidence that the benefits of post-secondary education are declining.

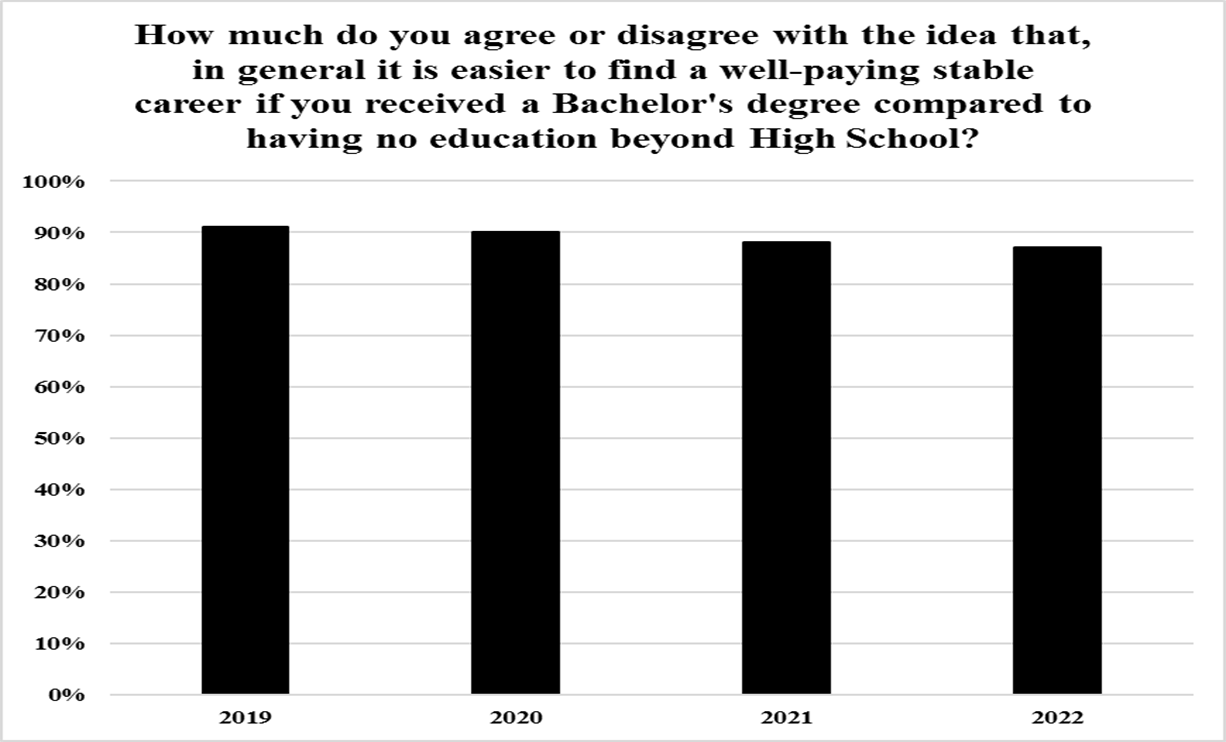

The second hypothesis is a bit outside my area of expertise, but it is whether or not the perception of the benefits of education have declined. This is survey work, and as an economist, my epistemological approach is primarily to observe human behavior, not ask folks their opinions. However, this survey from the New America poll suggests little change in the perception over time in the national data.

I’d be unsurprised if Hoosier results weren’t at least a little different from the national response. Since about 2015, Hoosier families have been fed a steady diet of bad information from the state’s Workforce Development apparatus. Their consistent misinterpretation of data would have you believe that Indiana had an excess demand for high-school only graduates and an excess supply of college graduates.

This nonsense infected the state’s Board of Education, which both loosened graduation requirements and re-positioned the state away from the “aspirational” education goals of Mitch Daniels. Beginning in 2016, the State Board began a broad focus on ‘occupational exposure’ that extended down to 6th grade. Thus, we had a state in which 12 year old boys were being propagandized into a such growth occupations as truck driver (negative wage growth for three decades).

Indiana’s focus on education abandoned educational excellence as a policy goal, and in many cases misled families about the benefits of post-secondary education. So, it’d be unsurprising if we perform worse than the nation as a whole in our perception of the benefits of college. Still, it seems unlikely that we have seen declines in perception of the value of a college degree that would cause such a sharp, immediate drop in college attendance.

The next hypothesis is that colleges have become ‘woke’ indoctrination factories, that are unfriendly to many students. When I first floated this hypothesis, several folks within education couldn’t believe I was serious. I am.

I personally know folks who were talked out of going to college because they thought the experience would run counter to the values they learned at home. And, no I’m not talking about deeply religious folks, but secular conservatives. I’d love to dismiss this argument, buy they have legitimate fears.

Colleges and universities are overwhelmingly progressive. Folks, the political divide among educators, and especially administrators isn’t even close. The number of studies available to document this is staggering. The most accessible summary comes from the American Enterprise Institute, but is also supported by survey work from Pew, and a growing chorus of concerned progressives. There are whole departments and colleges with zero conservatives teaching class.

To put this in context, I’m probably the most ‘conservative’ public professor in Indiana, and maybe second in the Midwest, behind Mark Perry. I’m a retired army officer and combat veteran, a Methodist, with photogenic children currently serving in the military, and a wife who’s a stalwart contributor to this community. Still, with those credentials, I’m not conservative enough to with a GOP primary anywhere in Indiana.

This is a problem for higher education. In a marginally normal world, there’d be a variety of voices coming from the professoriate. There isn’t. Moreover, the bulk of ideological bias comes not from classrooms, but from administrators. This is a place university leadership could easily invite broad perspectives onto campus. they don’t. The best you’ll see is a few libertarian speakers, mostly invited by an economics department. It’s a shame, and remediating this should be an important goal of higher education leadership.

All that said, I hasten to add that college graduates are far more conservative in behavior than their non-college peers. They marry at higher rates, stay married at higher rates, are more religious, have higher savings rates, and work more than their non-college peers. They are also beginning to display more ‘progressive’ political values. So, its sort of a mixed story on the ideological asymmetry that is a college campus today.

College should be a place that helps young people understand how to think, not what to think. Institutions within schools that do otherwise have no place on a college campus. But, this is nothing new, and cannot explain the sharp declines in kids heading to college from Indiana high schools.

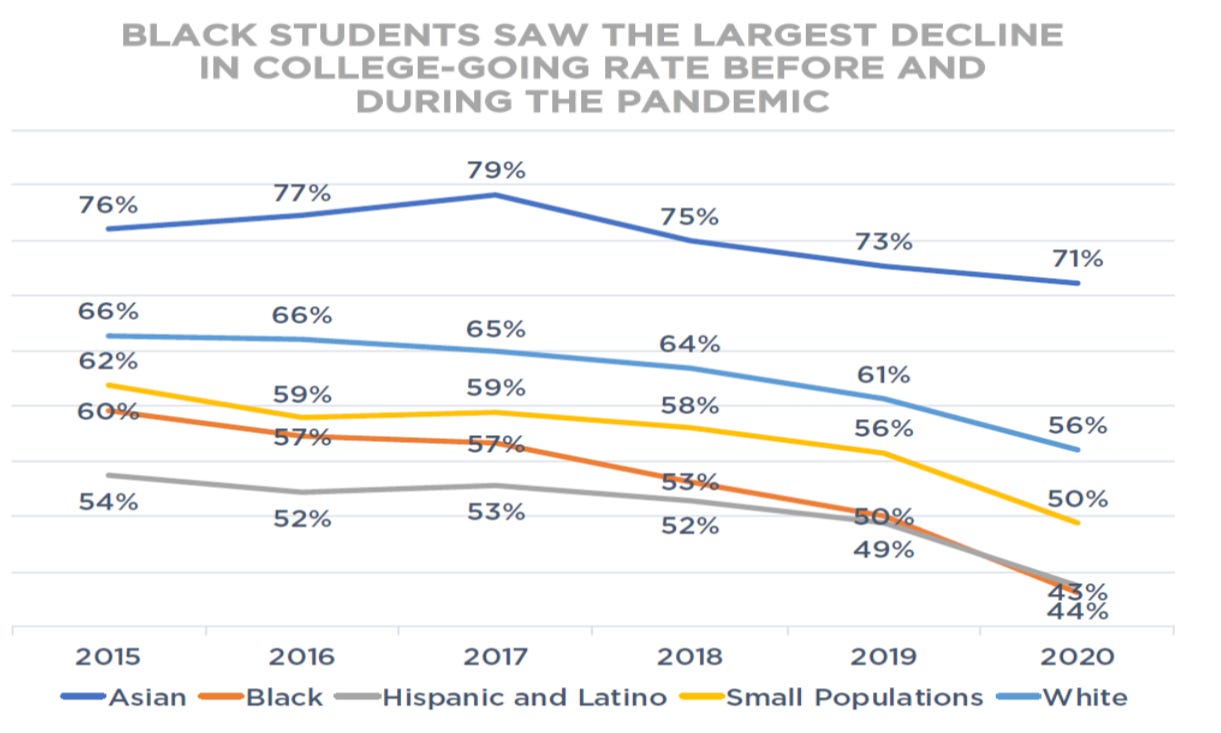

Source: Indiana Commission on Higher Education, College Readiness Report, 2022

This is especially true, since the largest declines came from African-American and Hispanic men. One might suppose that these groups would be the least affected by ‘wokeness’ on campus.

My next hypothesis is that the cost of college (tuition and fees) have risen. That one is the easiest to refute. Adjusted for inflation, the cost of colleges in Indiana peaked between the 11-12 school year and the 15-16 school year.

These data are from the National Association of State Budget Officers, deflated by the Consumer Price Index. An alternative measure is to provide a ‘time price’ of college. This is how long the average worker would have to labor to buy a year’s tuition.

Source: National center for Educational Statistics, various years, Bureau of Labor Statistics, and author’s calculations

Both measures provide the same result. Attendance has declined since college ‘sticker prices’ of tuition and fees have declined in real terms. Note, that the largest cost of college is the opportunity cost of not working, but prior to 2021-22, that has not changed enough to explain the drop in attendance. And, we probably shouldn’t count room and board in this calculation, unless you were going to live and eat for free if you skipped college.

But, here’s the big secret of higher education. Most students don’t pay a ‘sticker price.’ Colleges and universities ruthlessly price discriminate. Poor students, and those with some particular attribute that colleges want get scholarships. The rationale is that the ‘marginal cost’ of a student is near zero to a school. So, as long as the school can pay faculty and keep the lights on, adding another student is costless. So, most of these scholarships’ are just on paper. There’s no compensating money to operate them. The overall budget of the university is supported by tuition, some donations and state funding.

What is interesting about all this is where the decline in students are coming from. Because, if it is tied to tuition, then Indiana’s public university’s would not see meaningful declines. The loss of Hoosier students heading to college would come from private schools (where tuition remains high and rising) and out of state schools, which are presumably more expensive (I’ll explain ‘presumably’ in a moment).

So, where has the enrollment decline come from?

Source: Indiana Commission on Higher Education, College Readiness Report, various years

Holy smokes, its coming from Indiana’s public universities! Private school enrollment is actually up since 2015, and out-of-state enrollment has hardly budged. On top of this, the number of kids graduating from high school over this time is up substantially in Indiana — by more than 5,200.

How can this be? How can Hoosier public universities, which have declining real cost of tuition and fees be actually losing students? How come there’s no change in enrollment in private or ‘out of state’ schools? Easy, Indiana has substantially reduced support for public colleges and universities. The biggest cuts have come since 2006.

Source: National Association of State Budget Officers, Bureau of Economic Analysis, U.S. Dep’t of Commerce

This gets to the heart of the matter. Despite the declines in tuition cuts (or at least inflation adjusted cuts), Indiana’s colleges and universities have, on average, met the budget challenges from the legislature by reducing available scholarships. We know this from the ‘net price’ paid by first-time, in-state students. We have data only from the 2018-19 to 2020-2021 years, and here’s how actual (inflation adjusted) costs changed over this period for the ‘big five’ campuses.

Source: National Center for Educational Statistics, Bureau of Labor Statistics

Holy smokes again! The actual price for attending college in a year (tuition and fees for the average student) have dropped at Ball State, IU and ISU, but risen sharply at IUPUI and Purdue. The facts are even more stark when you compare the ‘sticker price’ change to the actual change at these schools.

All of a sudden, the miracle of Purdue’s tuition doesn’t look quite so miraculous. It is easy to cut the ‘sticker price’ when an increasing number of your students get no scholarship funding. Both Purdue and IUPUI are actually collecting more tuition money than in the past, a whopping $1,155 to $1,175 per student more.

Both schools can do this by changing their admissions profiles to simply accept a higher share of affluent students, who are willing to pay full ‘sticker price.’ That leaves the other schools in the state with lower tuition ‘yields’ per in-state student.

Of course, that has long been the strategy of Purdue, IU and IUPUI. Fill your dorms with students who can pay higher prices (like out-of-state students, and more affluent in-state students).

Presumably, they are doing what other states do and offer ‘scholarships’ to out-of-state students that magically reduce the cost of attending Purdue or IUPUI down to the in-state student rate. They all do that for most students, hence insuring an overall boost in revenues.

Now, this is fine for individual schools to pursue such a policy. I have no reason to expect that a well known school wouldn’t mind trading off their name to bring in more students. But, when doing so, there were some negative spillovers elsewhere. Purdue managed to convince the general assembly that they were efficiently delivering education, when they were not. The concomitant funding cuts to higher education have largely fueled a decline in support for poor students across the state. Thus, most of the lost college attendance has come from poor, mostly minority students in Indiana.

In the end, I think the collapse in college attendance in Indiana can have lots of small causes, that effect individual students. However, the one big cause is that state funding for higher education is, as a share of GDP or the state budget, a fraction of what it was even a decade ago.

So, to recap, the narrative goes something like this. Since 2015, Indiana has a stunning decline of in-state public university enrollment, amounting to >5,100 per year, or 12% of a high school cohort. But, the total number of students heading to private and out-of-state schools has risen slightly.

The wage and employment benefits of heading to college are effectively unchanged, while the ‘sticker price’ of college (total tuition) has declined. However, state spending has been slashed so heavily, that the ‘net price’ of going to college in Indiana has risen. In some cases substantially (Purdue and IUPUI).

Some schools (Purdue/IUPUI) benefit from this by admitting more middle/upper class students who don’t receive aid. Others (BSU, IU, ISU) suffer. The net effect is less available aid for poor students in our in-state public universities. Hence, a sharp decline in attendance in those demographic groups.

As I told the group at the University of Indianapolis last week, if you were to pick one way to cripple the long term economic prospects of an enemy, you’d reduce the share of kids who attended college. If you were really smart, you’d try to drive the smartest ones to universities in other places, where they’d be more likely to stay. That wasn’t the idea behind the large cuts in higher education funding. But, it is the effect. This problem is Indiana’s number one long term economic risk.

Sources

https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/reports/varying-degrees-2022/

https://www.in.gov/che/files/2022_College_Readiness_Report_06_20_2022.pdf

https://nces.ed.gov/

https://www.bea.gov/data/economic-accounts/regional

https://www.chmura.com/

https://www.bsu.edu/academics/centersandinstitutes/cber

https://www.nasbo.org/home

https://www.bls.gov/

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/

Wow, I really enjoyed this marshalling of facts and agree that reducing funding to public universities is a bonehead policy. However, I'm having difficulty believing that an increase in net tuition prices at only 2 of the 5 largest public universities is the most important cause of the huge decline in attendance.

Wow! This is an amazing compilation. I have wondered how Purdue had managed to hold tuition steady for so long, and several people said they did it by admitting more out of state students who paid higher tuition, but I have never heard about your conclusion that they are admitting more in state students from families who can pay near full price as well. Every state legislator should be required to read your essay.