The Long Tail of Hate:

The KKK, population growth and religious mix in Indiana’s counties 1860-2020

Summary: The Ku Klux Klan left a more than century long impact on Indiana’s population and demographics.

Timothy Egan’s book, Fever in the Heartland, chronicles the rise and fall of the Ku Klux Klan in Indiana. It is an absolutely captivating read. If you like social science, history, a tale with heroes and villains, or a mystery, this is a book you will love. I simply cannot recommend it enough.

However, Egan’s book made me wonder what research had been done on the long-term effect of the KKK here in Indiana. In particular, I wondered if counties with a large Klan presence saw a reduction in the number of Jewish, Catholic or African-American residents? I wondered whether there were there changes to voting patterns, or did exposure to the Klan reduce the economic prospects of the places they were located? And, if there were effects, how long did they last?

I am heavily invested in research on quality of life, and its role on population and employment growth in modern America. This work has led to some interesting findings regarding the KKK and its effects on quality of life and population growth in more recent times. So, I couldn’t help but wonder what the presence of the Klan might have done to communities in the aftermath of its rise and fall in the 1920’s. To begin the study, it is best to go through a quick narrative derived heavily from Timothy Egan’s book.

Egan’s Narrative of the KKK in Indiana

The original Ku Klux Klan largely rose and disappeared in the decade after the Civil War. Initially, the KKK was created to suborn efforts of reconstruction and terrorize newly freed African Americans and those who supported them. But the original Klan was short lived, existing as an important force only in the years of reconstruction that ended in 1877. The reason for this brevity was simply that there was no need for the secrecy of the KKK in the Jim Crow era. Terrorism of African-Americans was openly accommodated by state and local government. There was no need for masked secrecy.

Four decades of Jim Crow passed, and there was substantial effort to “bind up the Nation’s wounds” with reconciliation between combatants. This didn’t extend to those over whom the war was fought – the formerly enslaved peoples of the United States. But there was a very robust effort to make amends between those who fought.

50th Anniversary of Gettysburg, Library of Congress

The natural hatred that would accompany such a deep and costly war softened. The softening of that feeling came as many in the south sought to romanticize the war and antebellum period in ways that further entrenched Jim Crow, and its racialist controls.

In 1916, D.W. Griffith’s movie “The Birth of a Nation” provided a mythical portrayal of the KKK. The film was a smashing hit of the time, playing over five years across the country – including across Indiana. It was screened in Woodrow Wilson’s White House, which was among the most racist administrations in history.

Almost immediately, grifters saw an opportunity, and began revitalizing the Klan in America. This revival, it must be said, was a profit opportunity. One young flim flam man, D.C. Stephenson, saw the opportunity and became a reasonably successful Klan recruiter. But, the KKK didn’t really experience resurgence in the south. After all, no need to pay money and buy expensive Klan robes to terrorize African-Americans, when Jim Crow was the law. The greener fields for membership were in the Midwest — especially Indiana.

D.C. Stephenson, Ball State Libraries

Armed with a membership model that looked a lot like a pyramid scheme, Stephenson grew the Klan in Indiana from zero to more than 250,000 thousand members in less than five years. This was 30 percent of the native-born male population of the state.

With annual dues of $10, of which more than half went to Stephenson, he quickly became a millionaire in 1920’s dollars.

Under Stephenson, The Hoosier Klan was also effective in co-opting the National Horse Thief Detective Association. This group had recently become irrelevant due to the invention of the automobile — which Egan noted, replaced horses in the hearts and minds of Hoosiers and horse thieves alike. From this platform, Stephenson became the most important figure in the state. He recognized this, and began a process of capturing the GOP, and elevating the Klan to positions of power.

By 1924, the governor, speaker of the house and the majority of both the senate and house of Indiana belonged to the KKK. Along the way, Kokomo became site of the largest Klan meeting in history, and the Klan became more popular than any other fraternal organization in the state. The KKK in Indiana was pure middle-class populism.

Muncie Ku Klux Klan Meeting, Ball State Libraries

Stephenson, like so many other populists who followed, was unable to limit his debauchery. He appears to have raped his way across much of the Midwest during the early 1920’s. He was even caught by the Muncie Police, but was protected from arrest since most of them were also Klansmen.

Egan provides several examples of the KKK threatened African-Americans. Indiana was free from lynching’s during the 1920’s, but not the threat of Klan violence. In one example, the Klan paraded through Richmond, causing Louis Armstrong, who was recording an album in the city to flee. The great Hoosier jazz pianist, Hoagy Carmichael had travelled from Bloomington to Richmond to watch the session.

Louis Armstrong House Museum

The Klan also targeted Jewish populations, enough that a private religious census compiled in the Association of Religion Data Archives that had collected data on Jewish population and synagogues since 1890 didn’t register any Jews in Indiana in 1926. It was in the midst of anti-Semitic sentiments, though exactly why the data was not collected is unclear (to me at least).

The Klan also targeted Catholics. South Bend had several Klaverns, and was the hot spot for anti-Catholic sentiment. This broke out in 1924, in a street brawl targeting students at Notre Dame University. They fought back, with brains and brawn, besting the older thugs who showed up for the fight — thus giving their football team a splendid mascot – the Fighting Irish.

Notre Dame University

The KKK also embraced prohibition. This may have been useful in targeting Catholics,, who were more likely to imbibe than the incumbent population. Many of the protestant, native born Hoosiers were in denominations where alcohol was either prohibited or viewed poorly. Terrence Witkowski does a fine job of walking through the role of the KKK in anti-consumption ideology. Ironically, the Grand Dragon of Indiana, DC Stephenson seems to have been an alcoholic, or at least a plain old drunk.

Egan’s book offers vignettes across Indiana, with villains and better still heroes of all walks of life; private citizens, newspaper publishers, and prosecutors.

Stephenson met his match when he raped and tortured Madge Oberholtzer, a former Butler student and Indianapolis resident. Timothy Egan provides a powerful, yet sensitive account of this crime and its aftermath. Suffice it to say that following the rape and torture, she’d attempted suicide by poison, but the coroner ruled her death a homicide. The reason for this is that Stephenson savagely bit her during the rape, leading to fatal infections. All his money and influence couldn’t save him from her deathbed description of his crimes.

He was convicted, sent to prison, and Klan membership collapsed. From 1920 to 1930, the KKK in Indiana went from zero, to membership that comprised one in three native born men, to almost zero. Still, there was no widespread suppression of immigration or lynching’s in the 1920’s, anywhere in Indiana.

Egan portrayed the Klan as primarily a reflection of ‘know-nothing’ populist movement, embedded in widespread grift. He made a compelling case, which inspired the economist in me to ask the questions outlined at the beginning of this essay.

Egan’s research was both detailed and broad. He clearly read the newspapers, memoirs, as well as scholarly books and technical papers on the Klan in Indiana. His conclusion that the KKK in Indiana was more money-making enterprise than terrorist group is consistent with the much of the recent scholarship on the subject. These include a book by Leonard J. Moore Citizen Klansmen and an academic paper by two of the nation’s best-known economists; Roland Fryer and Steven Leavitt.

Those studies, and a couple more are an important element in understanding the long term effect of the KKK in Indiana.

Important Literature on the Klan and its Effect

Egan’s book is a fantastic read. He pulled off something quite unusual in this type of book. It is hard to put down, deeply learned but accessible to nearly all readers (I feel high school and older are mature enough to read the book). At the same time, he offers a narrative of the KKK in Indiana that actually enriches an academic reading that might follow. He is able to broaden the interpretation of the Klan, while recounting the details of consequence. If you read only one thing on the KKK in Indiana, it should be Egan’s book. If you wish to write a doctoral dissertation on the KKK in Indiana, begin with Egan’s book.

However, my interest runs past 1926. I want to know what the longer-term effect of the KKK was in the places it operated. To stare, I distill some of the technical research on the issue. Leonard J. Moore’s Citizen Klansmen provided a very readable academic focus on the KKK in Indiana. Much of the data I use, as did Fryer and Leavitt before me, came from his work.

Moore’s research offered analysis of the location, size of city, and membership by county. He also performed analysis of membership rolls for education and occupation. This is from his table 3.6, occupations of Indianapolis Klansmen (pg. 63), and involves two random samples from Indianapolis (N=500 for each sample). Similar data also exist for Richmond (where Hoagy Carmichael came to watch Louis Armstrong).

As Moore notes, the KKK was overrepresented in the lower white-collar and skilled occupations of the time. The cost of joining the Klan was significant, at $10. This was less than a decade after Henry Ford introduced the $5 a day wage scale for factory workers. By the early 1920’s the median employed worker was making $1.23 per hour. So, the $10 cost of Klan membership was more than a day’s labor for lower paid workers. That 1920’s $10 membership fee is equivalent to more than $175 today.

Moore’s empirical analysis found little evidence that occupation, geography or exposure to immigrants, Catholics, or Jewish residents explained different levels of Klan membership. Indeed, the southern counties of Indiana, which were geographically and culturally closer to Kentucky, had lower densities of clan membership in 1925.

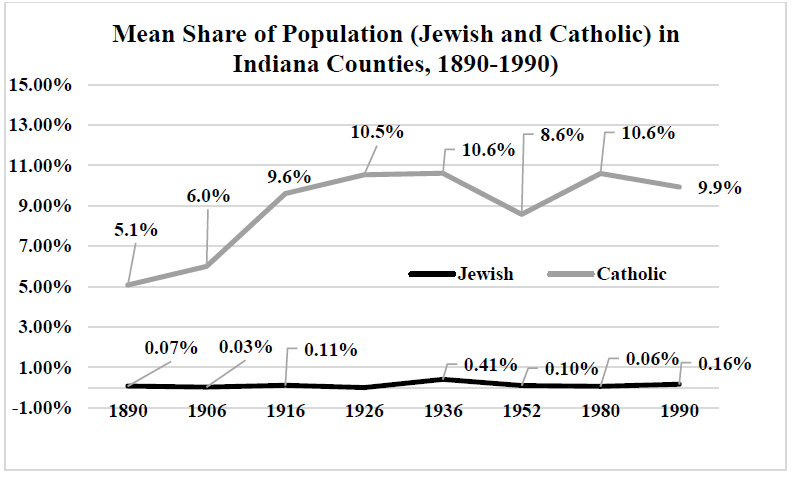

Moore made three big points based on an exhaustive analysis of the causes of the KKK. The first was that the rise of the Klan was not due to “a sense of conflict between White Protestant American and urban-immigrant America.” Many places the KKK thrived had few or no African-Americans or recent Catholic or Jewish immigrants. The African-American population is not readily available at the county level, without resorting to pretty time consuming IPUMS data. The religion data is available from the Association of Religion Data Archives. The share of the Catholic and Jewish populations, in the mean Indiana county is shown below.

Moore makes the case that the 1920’s KKK in Indiana and elsewhere were due to a “deterioration of a sense of cohesion, order, and shared power in community life, a process in which Indiana’s ethnic minorities played only a small role.” Page 189.

Perhaps Moore’s most salient point was that “the outpouring of ethnic consciousness resulted from the decline of community rather than conflicts with ethnic minorities per se is a second general conclusion having to do with where the Klan movement was centered.” Page 190.

His third argument focused on the timing of the KKK, in the immediate aftermath of World War One. He noted that “The Klan movement weas triggered in good part, not by the disillusionment with progressivism, but by a yearning to fill the void left by its demise. The great symbol of that desire was Prohibition. Support for Prohibition reflected the single most important bond between Klansmen throughout the nation.” Page 191.

This cartoon was just one of many that hailed the KKK as champions of prohibition.

This quote from Moore not only summarized the movement, is sounds shockingly contemporary: “Those who joined the Klan did so because it stood for the most organized means of resisting the social and economic forces that had transformed community life, undermined traditional values, and made average citizens feel more isolated from one another and more powerless in their relationships with the major institutions that governed their lives.” Page 189.

This doesn’t mean that racist and anti-Catholic sentiment wasn’t a force in the Klan. It was. The Fiery Cross, the official KKK newspaper on January 19, 1923 published an example an example featuring a Reverend William Henry Brightmire a Methodist pastor of Indianapolis:

"Remember this," said Rev. Mr Brightmire, "those accusers of the Ku Klux Klan don't know a thing about it. They have never been inside. Every once in a while, a bunch or Jews or Catholics or niggers get together, and damn the Ku Klux Klan but they don't know anything about it. I don't know anything about the Knights of Columbus, and 1 don't want to know anything about It. If it will just leave me alone, I will leave it alone." Rev. Mr. Brightmire illustrated “There was member of the Knights of Columbus in a town in which he conducted a meeting, he said, he was heard to curse the Ku Klux Klan. He was heard by 10 Klansmen, who happened to be near, "and do you know, in 10 days that man had to sell his business and move to another town.” As for the Klan in politics "We don't boycott," Rev. Mr. Brightmire hastened to explain. "Remember that, the Ku Klux Klan never boycotts anybody. Sometimes there is a person whom we treat to a little spell of letting alone."

As a lifelong United Methodist, this absolutely shocked me. For further reading, Paul Mullins blog offers a nice summary of the role of the pulpit in the rise of the KKK in the 1920’s..

Most people who joined did so not for the hate and bigotry, but for other reasons. Timothy Egan’s work treated that aspect of the KKK in Indiana with a great deal of nuance. That is a real challenge when covering the topic of the Klan. His review of membership includes examples of individuals pressured to join – which seems unsurprising given the financial incentives offered to recruiters.

Roland Fryer and Stephen Leavitt’s paper, Hatred and Profits: Under the Hood of the Ku Klux Klan, lays out the scale of this financial incentive. They estimated a bit over 22,000 new members a year during the heyday of its growth. They estimated that new membership alone brought the Grand Dragon of Indiana, DC Stephenson more than $925,000 (in 2024 dollars, per my calculations). The state sales manager (King Kleagle) earned over $410,000, while the Great Goblin (whom they label as the regional sales manager), would’ve earned over $205,000 per year. There was no good data available on the number of direct sales agents (Kleagles).

Fryer and Leavitt provide a graphical depiction of Klan organization, which I reproduce here.

Fryer and Leavitt undertook a number of empirical tests of potential causes, and voting effects of KKK membership. For my purposes, I was interested in their estimates of the effects of KKK membership and population. They used the migration of African-Americans and immigrants. I’ve reproduced their Table V here.

The are of interest is Panel B, Indiana. They use the county level share of KKK in 1924 from Moore (1991) as an explanatory variable on pre-treatment period (1910-1920) and between 1920 and 1930. The first set of estimates would allow some inference about both the presence of African-Americans and immigrants in motivating Hoosiers to join the Klan. The second would test whether the Klan led to less in-migration by African-Americans or immigrants (foreigners).

The models are first a simple test of KKK membership rates on migration, and second the same model with the addition of controls. In the simple model (1, 3, 5 and 7) there is a clear pattern of a negative impact on African-Americans and a positive impact on foreigners. However, all of these effects disappear when other control variables are introduced.

Fryer and Leavitt interpret this as a ‘hint’ of effects, with weak statistical certainty. As with the Jewish and Catholic population, African-Americans comprised a small, 2.75 percent, share of the Hoosier population in 1920. It rose to 3.46 percent by 1930, as the Great Migration to northern factories began in earnest.

They conclude their paper with this:

“The Ku Klux Klan symbolizes the extremes of race and religious hatred in America. Since its inception in the months after the Civil War, the Klan’s organization, mission, and power have varied tremendously, with membership and political influence peaking in the mid-1920’s when over a million Americans were members. Contrary to the conventional wisdom, however, our statistical analysis shows little evidence of a relationship between Klan activity and black or foreign-born migration, lynching’s, or politics during this time period. Rather, the 1920’s Klan is best described as an enormously successful marketing ploy: a classic pyramid scheme, officials at the top getting rich off the individuals at the bottom, energized by sales agents with enormous incentives to sell hatred.” Page 1924.

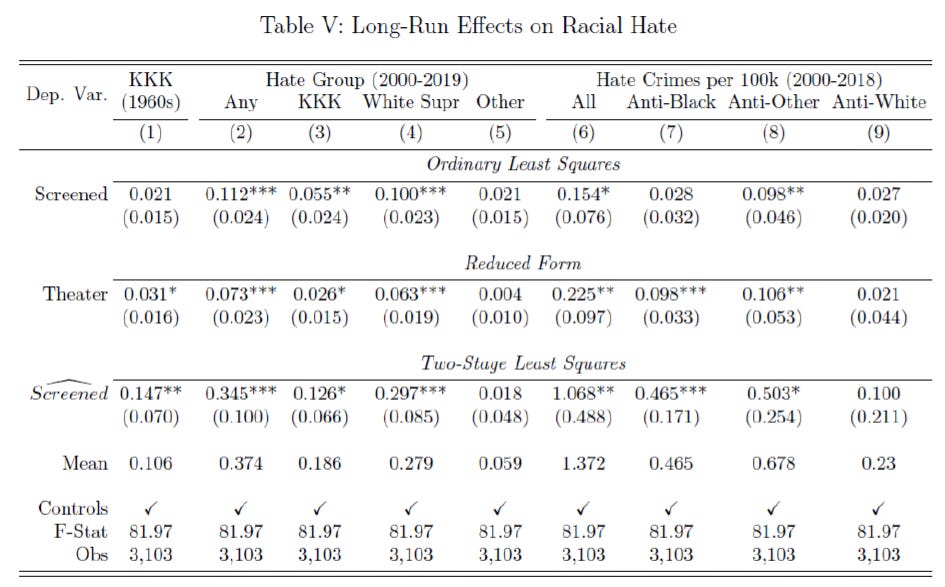

Another, newer study by Desmond Ang used the screening dates of The Birth of a Nation as a data point to measure the subsequent spread of racial violence. Using the date of screening, the size of the theater in which the movie was screened, he empirically estimated the growth of the KKK in the 1920’s, and hate crimes against African-Americans, other minorities and whites. He also used this measure for long-run effects, such as the presence of any hate group, the KKK, other white supremacists’ groups and hate crimes (as measured from the FBI Uniform Crime Report).

Perhaps the most visually appealing aspect of his paper is this event-like analysis of the showing of Birth of a Nation and subsequent expansions of the KKK in US Counties. Here, is the mean number of Klaverns (a local branch or meeting place of the Ku Klux Klan).

This estimate shows how, over time, the screening of Birth of a Nation led to increased presence of a Klavern. This is strong support for his hypothesis that more exposure to the racial stereotypes and racist messages in Birth of a Nation acted as fuel for the expansion of the KKK in the 1920’s.

My questions involved long run effects, and Desmond Ang’s work focused on the presence of hate groups (the KKK and others) along with reported hate crimes in the 21st century, more than 80 years after the last of the initial screenings of Birth of a Nation.

His empirical analysis focused on carefully establishing causal connection between screenings and subsequent measures (late KKK resurgence, hate crimes, etc.). I reproduce his empirical table on long run effects here.

Ang used three different models to evaluate the robustness of his results. We are interested in examining the statistical certainly (denoted by an increasing number of asterisks) along with the size of the labeled values. Across the board, we see evidence of long-term negative effects of the screening of this movie, or the size of the potential audience on these measures of hate.

These are compelling results, that speak directly to the potential long run effect of viewing Birth of a Nation on the membership of hate groups, particularly the KKK and hate crimes. Again, what interested me by reading Timothy Egan’s book was how long did the effects of Indiana’s 1920’s KKK explosion last, and in what ways did they manifest themselves.

The Long Run Effect of the KKK in Indiana

There have been three waves of the KKK in the United States. The first was during Reconstruction, the second during the 1920’s and the third during the Civil Rights period. Indiana only had a measurable Klan presence in the 1920’s. This map, from data provided by Virginia Commonwealth University illustrates the reported Klaverns in the US derived from newspaper and KKK record.

The data on Klavern’s from the University of Richmond is the primary source for most of these studies (Ang’s and mine in this essay). This source lists the number of Klavern’s and also lists ‘named Klaverns’ which received a particular name, typically a geography or well-known favorite son. This is an example of the Muncie Klan, in The Fiery Cross, the official Klan paper.

From the Hoosier State Chronicles

The named Klavern variable may be useful in that it likely reflects a more active Klan community. I hypothesize that the intensity of members is not just measured by membership, which was after all, a pyramid scheme. So, higher membership numbers could as easily come from a local Klan that was less objectionable, less active and less virulent in its stances against African-Americans, Jewish or Catholic residents or immigrants. A named Klan potentially offers a better measure of the intensity of Klan membership.

Data on Klan membership comes from Moore’s 1991 book. The Census provides population data for the decennial periods. Fryer and Leavitt provided a complete answer regarding the short-term effect on African American residents. I won’t replicate that work, besides noting that the cost of obtaining county level demographics from the 1920 and 1930 Census is substantial.

I am interested in the effect of the KKK on Jewish and Catholic residents as well as overall population change. The Association of Religion Data Archives provides very accessible and well organized and documented data on religious participation. This includes hundreds of denominations, at the county level. However, they are reported for different years (e.g. 1916, 1926 and 1936, etc.) This, to make comparisons, I must interpolate data from population to match the religious census data. I do so linearly, but the years are not always a decade apart. I actually have 1890, 1906, 1916, 1926, 1936, 1952, 1980 and 1990.

The data are not ideal, but this is all there is available, which likely explains why there isn’t a peer reviewed paper on this. Moreover, the Jewish data was not collected in 1926, perhaps because of the presence of the Klan. This introduces some technical problems I will gloss over in this essay.

My first empirical test is simply a two-way fixed effect, difference-in-difference estimator of the effect of KKK membership share of the population, the Klavern’s per capita and the named Klavern’s per capita, on the share of Catholic, Jewish and both, from 1890 to 1990 in Indiana’s counties.

This is a basic causal inference estimator, that is best used for this sort of modeling, where there isn’t a large, homogenous treatment and control group, but rather a heterogenous shock across most counties at the same time (homogeneous timing).

The Two Way Fixed effects means that I have a single control variable that accounts for variation that is common to each county throughout the century that I have available data, and one fixed variable for each year. For the Jewish and ‘Both’ categories, I also dropped the time series fixed effects, and substituted a dummy for the missing Jewish congregational membership data that year. The results were effectively identical. I’ve also used White’s panel clustering for standard errors, and tried alternative specifications to test linearity of the models.

This is more technical discussion than I normally offer for this type of essay, but I hope it is sufficient to satisfy my econometrician friends, and let everyone else at least partially understand the challenge of doing this type of research. It should also let you know why it is best to look at several studies, with lots of different tests and model specifications before drawing very strong inference.

There is just not good evidence that the Catholic or Jewish share of the population decline as a consequence of the share of residents in the KKK or the number of Klaverns within a county.

However, the named Klavern per capita data enjoys statistical significance, and a relatively large effect at the margin. With all the caveats of these data presented above, there’s a hint that the intensity of the organization is driving the negative effects on Catholic and Jewish share of population. I also included a spatial variable of the KKK, which is the weighted average of each Klan measure in the contiguous counties.

Note: Formally, these variables are first order contiguity matrix weighted, with White’s panel standard errors.

All these estimates include ‘own county’ KKK share or Klavern’s per capita, and all the models perform similar to those in Table 2. What is striking about these results is that all are negative, and many are close to traditional levels of statistical significance. Indeed, traditional statistical significance in all these estimates are sensitive to assumptions made about the nature of the standard errors.

As a side note, that means two researchers could make very modestly different assumptions about the distributional properties of the standard error (which cannot easily be checked) and draw different conclusions about the statistical reliability of these results. This is why it is important to understand the literature, not just a single study. There is a strong publication bias towards statistically significant results. The literature on these issues will often include several estimates, using different data (if available) including different control variables over different geographies and times. A bit more thoughtful review of this is available from Diedre McClosky and Stephen Ziliak here.

For the purposes of this work, we can say, as Fryer and Leavitt did before us, that the KKK presence in Indiana had negative consequences on minority populations. Their work focused on short term effects on African-American and foreign migration into Indiana counties. We examine longer term effects on religious minorities (Catholics and Jewish residents).

Table 4 illustrates the effects from the estimates presented in Table 2 and Table 3. This table reports the average population of each of the categories between 1890 and 1990, and two different effects estimates. The first of these is the effect on each group of one additional named Klavern appearing during the 1920’s. The second is the same increase in the average of adjacent counties.

At first blush, theses effects seem modest. They aren’t. An additional named Klavern would reduce the countywide share of Catholics by 0.57 percent, but that is 6.2 percent of all Catholics, or equivalent to one in 16 Catholic residents. The effect on the Jewish population is even larger. A single named Klavern in a country reduces the Jewish share by what might appear to be a modest .03 percent, but that is nearly one in four Jewish residents (23.1 percent).

The effect from adjacent counties is even higher, but has a more nuanced interpretation. The adjacency measure is the named Klaverns per capita in the average of all adjacent counties. So, an increase of one on average, would be the equivalent of between 1 and 7 additional named Klaverns (because that is the range of adjacent Indiana counties).

My interpretation is that the spread of named Klaverns across a region of adjacent counties was worse in terms of minority populations than simply having one in an own county. This might seem counter intuitive, but living in a region where the intensity of Klan activity was higher (through named Klaverns and heavy activity in surrounding counties) created a worse climate for targeted populations (here, religious minorities), than simply having a local Klavern that might exist quietly, as a money making organization rather than a political or cultural entity.

Recall, my argument is that KKK membership was so ubiquitous, and a substantial number of members were only peripherally associated with the Klan, that simple membership shares didn’t well portray the intensity of Klan feeling.

Moore, 1991

The presence of a named Klavern, which were present in about 30 percent of counties reflected a more intense, or at least better organized Klan. The effects described above represent the average effects from 1930 through 1990 the duration of our sample. So, the presence of a named Klavern in an Indiana County affected the Catholic and Jewish populations substantially, reducing them by an average of 6.2 percent and 23 percent over the 60 years following the opening of these Klaverns in Indiana.

Fryer and Leavitt provided African-American data in 1920 and 1920, reporting a modestly negative and statistically weak effects on migration of both African-Americans and Foreigners. Their results are similar in that way to ours. But, it is also useful to simply examine how the number of named Klaverns effected long term African-American population in Indiana.

This graphic, which omits counties with no named Klaverns, and makes pretty strong hints at a long run negative effect of the more organized, better known Klaverns on African-American share of the population.

Importantly, the work by Fryer and Leavitt, and my estimates in Tables 2, 3 and 4 use causal methods. The graphic above is correlative, since I don’t have readily accessible demographic data for early Census years. Moreover, Fryer and Leavitt, report declining African-American migration in the 1910’s in counties that had higher KKK share of the population in the 1920’s. This could be a classical problem of capturing the pre-trend and a attributing it to the treatment effect of Klan membership. However, they also introduce control measures that would account for African-American migration, which then erases the effect of the later Klan membership.

Notably, if we are trying to attribute Klan presence to a malevolent environment for African-Americans, Catholics or Jewish residents, the fact that some were leaving in the 1910’s, is hardly evidence to the contrary. This is particularly true since this decade was coincident to the release of Birth of a Nation, and other potentially influences of racial and ethnic tension.

But, we are not at the end of the ability of analysis to reveal the effect of the KKK on the long term prosperity of Hoosier Counties.

My next step was to perform an event study of KKK membership on long run population. This is more straightforward, since I have annual data from 1860 through 2020 and a discrete Klan presence between 1920 and 1930. This is long enough to perform an event study, which was not possible with the religious data.

This event study method is often used to measure stock returns following an earnings announcement or some other type of shock. I can use only a limited number of observations to illustrate the impact. The results are plotted with coefficients before, and the cumulative effect after the KKK expansion and decline of the 1920’s. The goal of this is to measure the effect of the KKK presence on the general population, not just targeted religious minorities and African-Americans.

The reason for this is fairly straightforward. The incumbent white population in Indiana was not a monolith. Civil War veterans were in their late 70’s and early ‘80’s, or about as old as today’s Vietnam Veteran’s. The expansion of a group founded by Nathan Bedford Forrest wouldn’t have sat well with many of them. Younger citizens had been taught to put regional differences aside. Timothy Egan highlights one such veteran and his efforts to oppose the Klan. Read his book.

Likewise, Methodists were heavily involved in the abolition movement, but the language of Reverend Brightmire quoted above would not have set well in many congregations. There were also religious minorities, Quakers, and others with very mixed feelings on the Klan. Indiana’s most famous poet, James Whitcomb Riley wrote an early poem critical of anti-Catholic, anti-Irish sentiment. His work was heavily quoted by George Dale of the Muncie Post-Gazette in his heroic efforts to disable the Klan. Again, Egan tells the story impeccably.

The presence of the Klan could well have had negative effects on population beyond those on African-Americans, Catholics or Jewish residents. Moreover, much of population growth in the immediate post 1920’s period was job related. Businesses who wished to access labor would be far less enthusiastic about a local environment that pushed away potential workers, thus driving up labor costs.

The effect of this is an empirical question, for which I have some answers.

My event study reports negative effects of the presence of the Klan (here KKK share) on overall population for more than three decades. At its worse, a one percent increase in the KKK share (of native-born adult men) reduced population in a county by half a percent. I cannot fully estimate the later effect, but give3n that the mean county had a bit over 19 percent of its men in the KKK, the lower local population due to Klan activity is significant.

The next graphic depicts the event study for a named Klavern. As is visually clear, having one resulted in substantial negative, long-term effects on population. The marginal effect on counties was enormous. Leonard Moore’s data reports only six counties where the total Klan population exceeded 4,000 residents. The median county Klan membership was 1,327.

This event study reports a remarkably high negative effect. For the median county in the 1920’s, every additional Klan member resulted in 10 fewer residents than they would have had absent the Klan in the 1920’s. For much of Indiana, including Muncie, the immediate post-World War Two period was not a halcyon period, but a demographic peak.

Conclusion and Extensions

It is impossible to view these results and fail to conclude that the Ku Klux Klan in Indiana did not play a part in economic decline for parts of the state. While the 1920’s through the 1950’s saw increased industrialization and employment growth, Indiana would’ve been a larger and more diverse state without the Ku Klux Klan affect a full century ago.

This really shouldn’t surprise anyone. A ubiquitous message from the Klan was we don’t want immigrants, Catholics, Jews or African-Americans to move to or thrive in our communities. It would be remarkable if potential residents didn’t heed those messages when selecting where to move. The America First movement was drawn from the same intellectual well as the KKK. It still does, but the target of hate has simply changed.

Hoosier State Chronicles

Finally, my interest in the KKK as a contemporary area of study wasn’t just motivated by Timothy Egan’s book. For the past decade I’ve been researching quality of life and population growth in the United States. Some of that work appears here and here in The Country Economist.

In that work on micropolitan places with Dr. Emily Wornell and Dr. Amanda Weinstein, we isolated outlier counties for which to target qualitative research (see a nontechnical version published by Brookings here). One county had very low Quality of Life on our measure, but was geographically blessed. It had temperate weather, good access to large metropolitan areas, an airport, a state university, decent schools and proximity to hills and water features. In short, it had nearly everything that should boost quality of life (according to our research).

We picked this place to visit, as one of our three definitive underperforming quality of life locations. That was where we felt qualitative research would reveal something important. We decided to run a quick web search on the place, only to find it was the national headquarters of the Ku Klux Klan.

Courtesy of the Museum of American History, Cabot Public Schools

Encyclopedia of Arkansas

In one sense, that finding boosted our confidence in our work. We undertook a national, county level hedonic pricing studies and Mincerian/hedonic wage models on aggregate data to build a single measure of quality of life in the Rosen-Roback approach. In that 50-variable model of 3,143 counties, we found an outlier that pointed us to the KKK of the 2010’s. That is very strong evidence that the Rosen-Roback explanation for quality of life is robust, and that our use of aggregate county data are a good tool.

Indeed, we have Klavern data nationwide (not KKK share). This permits us to evaluate whether or not the KKK presence from the 1920’s affects quality of life today. In the results using, quality of life measures from Weinstein, Hicks and Wornell (2022), we find that yes, the presence of a Klavern continues to impose a cost on quality of life in a region.

However, in another sense, this is deeply troubling. Only a tiny share of Harrison County residents belong to the Klan. It is a modest refuge of hate and terrorism in an otherwise beautiful part of America that should be thriving, but is not. The long term prognosis for Harrison, Arkansas is not good.

The adult members of the 1924 Klan have all died, yet the economic and demographic impact on Indiana continues to be felt. This effect should not be so prolonged. There has been no measurable KKK activity in the state subsequently (no Klaverns noted). Yet the damage from a century ago remains.

It is fair to say that whatever brought people to its membership rolls; hate, fear, coercion or revenues, the KKK has helped keep places poor, under populated and trapped in the shadow of an evil ideology. The long tail of hate plays a relentless role in weakening local economies, reducing population growth and dampening prosperity. A century later, the effect remains, on population, demographics and quality of life.

Note: This work may ultimately be put into a format for peer reviewed publication. But, given the results, I did not wish to sit through a multi-year publication lag. Anyone wishing to work on these topics, or seek the data, please feel free to contact me.

Sources

Chapter locations for the Third KKK (during the 1960s) are publicly available to download at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/WKJJ3Z

Ang, Desmond. "The birth of a nation: Media and racial hate." American Economic Review 113, no. 6 (2023): 1424-1460.

Fryer Jr, Roland G., and Steven D. Levitt. "Hatred and profits: Under the hood of the ku klux klan." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 127, no. 4 (2012): 1883-1925.

Kneebone, J. and S. Torres. 2015. Data to Support the ”Mapping the Second Ku Klux Klan, 1919-1940” Pr oject. History Data. Virginia Commonwealth Klavern Data https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/hist_data/1/.