School Choice and Student Transfers

Was school choice good for local public school enrollment?

Indiana has the most expansive school choice legislation in the country. Since 2011 there’s been full open enrollment statewide (space allowing), a growing number of charter schools and a private school voucher program. Indiana’s experience with this school choice is important to understand given the widespread interest in similar policies around the nation.

My colleague Dagney Faulk and I just published a paper on school choice and student transfers in Indiana. The goal was to understand the school related factors that contributed to the movement of kids in and out of schools. Unlike earlier studies of the matter, we looked at all three kinds of school choice (inter-district transfers, charters and private school vouchers).

We have enrollment information on private schools, but we don’t know the residence of those who don’t take vouchers. Likewise, we don’t have location or numbers of home schooled children. These aren’t unimportant matters, just outside the scope of this data set and study.

Our study looked at the 2018-19 year (pre-COVID) year, examining total enrollment, not just a one year change. We’ve published on this issue before, examining the savings of school choice to taxpayers. The more important issue, at least for the contemporary debate about expanding school choice is not about cost savings. Rather, it is about the ability of families to choose schools, what motivates those moves and what happens to the schools they leave and those they move to.

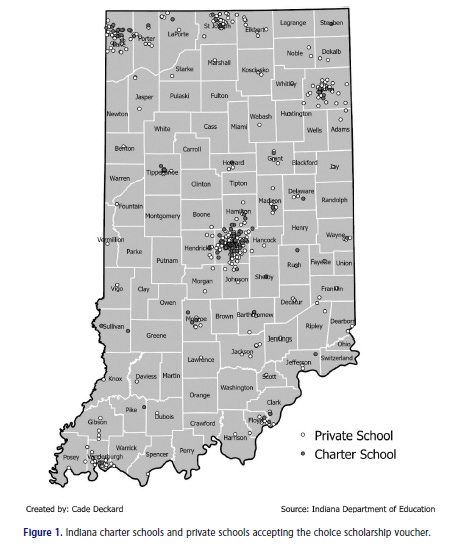

We begin by mapping the options available for school choice. Here we map two types of schools; charter schools and private schools accepting state vouchers )Choice Scholarship).

As should be obvious, there are sporadic geographic options for charter schools, with nearly all the schools clustered in a few larger cities (Chicago area, Ft. Wayne, Indianapolis, Evansville, and college towns). Charter schools may be ‘chartered’ by state universities, municipalities or school corporations. Much of the recent growth has been charter schools within existing large school corporations.

Charter schools within these larger, urban schools specialize in some key aspect that wouldn’t be feasible for a local public school. Examples are all-girl academies, STEM and college preparatory programs.

Private schools are more geographically dispersed, but many counties do not have a private school. The next map, from our choice cost study mentioned earlier illustrates the 289 school corporation boundaries by enrollment. Note how few have more than 5,000 students, and how many have fewer than 2,500. Importantly, these are not all rural schools. The Muncie Metropolitan Statistical Area (Delaware County) has seven school corporations. four are fewer than 2,500 and two are 2,501-5,000. When this study was performed the MCS system was over 5,000 students.

The summary statistics of school choice offer significant insight into the choice decisions surrounding schools. I’ll offer a bit more political economy analysis here than in the academic paper, but suffice it to say it speaks directly to the likely effects of the burgeoning school choice debate underway in the U.S. today.

School Choice in Indiana effectively dates back to 2001, and the authorization of state universities to charter schools. Prior to that you could home school, pay for a private school or pay tuition to attend another public school. We don’t have good data on home school or transfer, but believe that almost all of the inter-district transfers were due to parents working (teaching) in schools outside their home school district (corporation in Hoosier parlance). From 2000 to the 2020 student count, enrollment in Indiana declined modestly from 1,122,821 to 1,111,333 students, or just 1 percent.

In 2000, 12.00 percent of Indiana’s students attended private schools. That was 134,757 students, none of whom had any state funding for tuition. Over twenty years of evolving school choice, private school enrollment dropped to 55,348 or 5.1 percent. Of those, 36,204 had school choice scholarships. That means that the number of Hoosier students paying their own tuition to private schools plummeted by 85.7 percent to just 19,144 students.

This answers at least one key question about the effect of full school choice on private schools. They are devastating to enrollment. It may be that without the choice scholarship, we’d have a dozen or fewer private schools remaining in Indiana. As it is, few, if any, meet the minimum efficient scale we estimated for public school corporations in the state (though that MES is likely lower for private schools). So, where did students go?

In 2020, 13.8 percent of students participated in school choice or attended private schools without a choice scholarship. This is an increase of 1.8 percent of students, but where they attended school changed dramatically. In 2020, 34,733 students attended independent charter schools (those authorized by universities or municipalities). This comprised 3.1 percent of school choice. As noted above, 5.1 percent, or 55,348 attended private schools, 65.4 percent of whom received choice scholarships to attend those private schools. However, inter-district transfers accounted for 62,860 or 5.7 percent of students.

From pre-school choice days (2000) to 2020, the share of Hoosier students who chose not to attend schools in their own local public school corporation grew by 3.8 percent. But, the share of kids outside traditional local public schools declined to 8.3 percent. Inter-district (corporation) transfers accounted for the gap.

What that means is that despite a modest decline in student enrollment statewide from 2000 to 2020, traditional public school enrollment actually rose by more than 62,000 kids. After choice came, and schools began competing for students, the winners were local public schools.

That begs the question, what caused students to leave? To answer that question, we ran three empirical models of student inflows and three of outflows. This is a representative regression output, with summarized explanations below. The models I, II and III differ. Model I is all corporations, with all corporation variables. Model II is the same sample, but includes the average of adjacent school values and Model III excludes the three big schools (Gary, Indianapolis and South Bend).

We concluded from the outflow model that:

As the test score pass rate increases, fewer students transfer out of their district of residence to another traditional public school. A one percentage point decrease in test scores is associated with three to four outgoing transfer students.

The effect is similar for private schools: a one percentage point decrease in test scores is associated with an increase of two to four outgoing transfers. There is no statistical evidence that test scores influence transfers to charter schools or aggregate inflows.

These results suggest that student achievement is an important determinant of student outflows to another public-school district and private schools.

Demographic factors also influence aggregate transfers.. In the typical public school, one percentage point increase in free and reduced lunch students is associated with a six to eight additional outgoing student transfers from public to private schools.

The percentage of free and reduced lunch students has a positive effect on transfers to private schools only until the percentage of free and reduced lunch students is 15 percent. After that, the impact begins to decrease. This likely occurs because students in schools with high percentages of free and reduced lunch are less likely to be able to afford private schools even with vouchers.

The share of free or reduced lunch students is not a significant determinant of aggregate transfers between traditional public school districts or between these districts and charter schools.

The race and ethnicity of students influence transfers. Traditional public school districts with higher shares of African American students have more transfers to other public school districts and fewer transfers to charter schools.

The percentage of African American students increases outgoing transfers at a decreasing rate. We do not know the race of transfer students to know if African American students or students of other races are transferring out.

The percentage of African American students has an increasing effect on outgoing transfers to other public schools only until the percentage is 40 percent. After this point, the number of transfers begins to decrease and approaches zero transfers as the percentage African American approaches 80 percent.

In contrast, as the percentage of African American students in a public school increases, transfers to charter schools decrease but at a increasing rate as indicated by the squared term.

In the typical public school, a one percentage point increase in African American students is associated with a decrease of 14.6 transfers to charter schools. However, outgoing transfers would approach 39 students in the district with the maximum percentage of African American students.

Importantly, When Indianapolis Public Schools, Gary Community School Corporation and South Bend Community School corporation are removed, the percentage of African American students is no longer a significant determinant of transfers from public to charter schools likely reflecting the low percentage of African American students in most school districts in the state.

The share of Hispanic students has no impact on transfers between traditional public school districts and inconsistent results across the three specifications for transfers to charter and private schools.

Other factors, such as school size, median household income and the availability of charter and private schools affect in/out flows of students. One additional charter school in a district is associated with 430 additional transfers from public schools to charter schools in the total sample. If the districts with the most transfers are excluded from the sample, the impact is still positive but lower at 86 students. The impact of private schools is smaller. An additional private school in a district is associated with 40 to 50 transfers using vouchers.

We also find that transfers to another public school district (outflow) also increase with the number of charter schools in a district. This suggests that families who are dissatisfied with their public school district of residence, exercise all options available. The magnitudes of the coefficients suggests that charter schools attract the most students followed by other traditional public school districts. The number of charter schools in surrounding districts is negatively related to transfers out of a public school district, which suggests that if charter schools are available they capture students that would have transferred to another public school district.

But, when IPS, Gary and SB schools (which have the most charter schools in their systems) the number of charter schools in a district is no longer a statistically significant determinant of transfers between public schools, but the number of charter schools in nearby districts is significant. This suggests that the number and proximity of charter schools is an important determinant of the transfer decision for families.

In the inflow model, fewer variables matter. Here, distance from a school corporation matters. Schools with higher share of Hispanic students reduces inflows, and higher state spending in surrounding schools reduces inflows. This latter point is likely due to the state formulary which pays more for poorer districts, and poorer students lack the transportation options for choice.

Overall, the issue of the difference between inflow and outflow models is that outflows are concentrated in just as few places, while inflows are far more geographically disparate.

We conclude by noting the evidence we gathered has implications for poorly performing districts. Our results imply that low achieving districts lose a large number of students and gain a small number, which results in a net loss in the number of students and state funding for many districts. For example, school choice resulted in net losses of 21,734 students in Indianapolis (47% of the residential enrollment base), 7,414 students in Gary (62%) and 7,078 in South Bend (30%) during 2018–19. Altogether this net outflow of students cost these schools $200 million in funding per year. That money went to another school.

Beyond the school level fiscal effect for poorly performing schools, there are obvious benefits to public schooling in general. This evidence goes a bit beyond the scope of our paper, but hints at why school choice legislation is surging nationally. Here are some stylized results of our work.

Families like choice, and the more choice they have the more they like it.

The biggest effect of choice legislation in Indiana was for families to substitute a public school for private school. Private school enrollment in Indiana plummeted by more than half after school choice.

The biggest effect of school choice, in terms of numbers of students was inter-district (corporation) transfer from lower to higher performing public schools.

Interestingly, poorer performing public school corporations appear to have been the largest new developers of charter schools. Many of these seem successful in stemming loss from their districts (corporations). The innovation from IPS and Gary alone are valuable policy outcomes from Indiana’s experience with school choice.

School choice also offers some insights about the value families — especially poor ones — place on school choice. In Gary, 62 percent of students have taken advantage of school choice, and a substantial share of remaining students are in one of Gary’s charter schools.

For obvious reasons, students participating in choice options mostly have to provide their own transportation to school. I ask the reader with children in school to muse upon the logistical challenges of any family in participating in choice. This represents a substantial cost and personal sacrifice for 6 in 10 families with school children in Gary.

There is an obvious rush to adopt school choice legislation across the nation. The proposed legislation appears linked to several factors, many of which emerged during the pandemic. Our paper, and more importantly, Indiana’s experience should be helpful in gauging the effect of that new legislation on schools across the country.

Legislators need to consider the effect on private schools. I suspect that some sort of choice scholarship is essential to maintaining private school options in many places. Though, I don’t have good insight on what the thresholds of those scholarships should be. Second, public school corporations should be able to implement their own charter schools. They should be placed on equal footing to innovate in education. Finally, high performing public school systems are likely to benefit from school choice in terms of enrollment. Poorly performing schools will lose students. As an economist, it is difficult to find fault with these types of outcomes.