In this short post, I will summarize some thoughts about our state (and Midwest) obsession with manufacturing jobs. To begin, I want to remind readers this is about state and local public policy, not the private sector. My criticism isn’t of manufacturing firms, but of the communities and elected leaders who believe that manufacturing employment will grow in their state and communities.

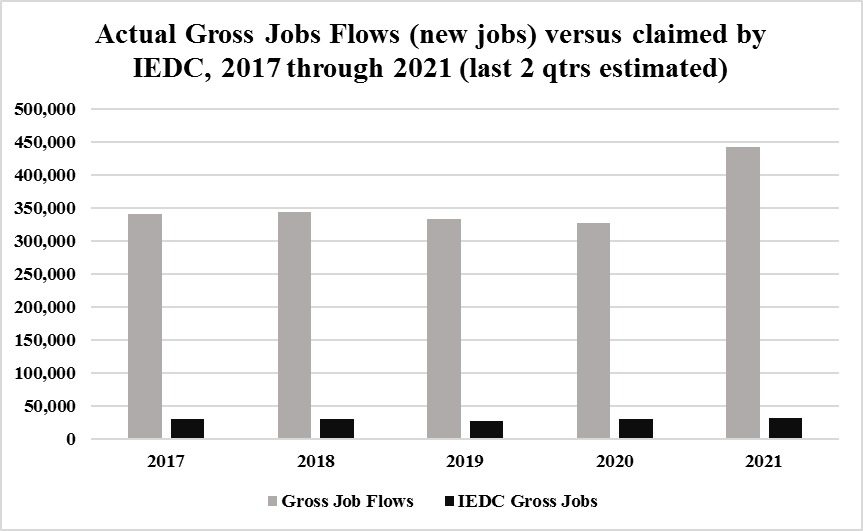

I begin by noting the focus on manufacturing employment seems to flow from the focus on economic development efforts. Here I illustrate the paucity of understanding those data provide. The Indiana Economic Development Corporation announced five record years in which they announced between 27,000 and 32,000 ‘promised’ jobs to Indiana.

Political leaders, such as Governor Eric Holcomb seem to think these data possess some meaning about the economy. That’s just not so. Actual new jobs created each year in Indiana are ten times higher (these are gross job flows). So, on a darned good year, IEDC might notice 8% of the gross job flows into the state.

(Note: That is not a critique of IEDC, which is a small organization, with a modest budget. They perform a number of critical roles within the state, typically with great professionalism. This is a criticism of those who think the job attraction efforts at IEDC reflect a large share of state employment growth.)

These data are from IEDC annual reports and the Quarterly Workforce Indicators. Since I use firm level, and not individual data, this actually overstates the role of IEDC.

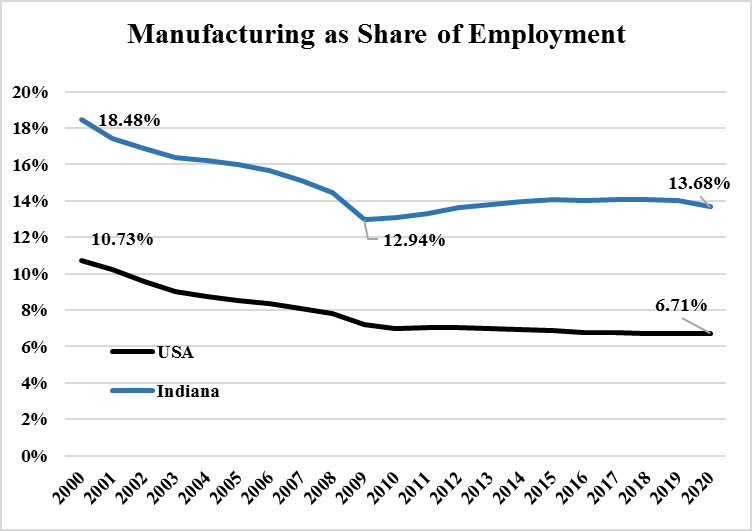

Over the past 20 years, manufacturing employment as both a share and in total has declined. From the end of the Great Recession through 2019 (when factory jobs peaked in Indiana) was the longest factory expansion in US history. Even then, factory jobs stayed static.

Factory employment is once again in decline as automation reduces the demand for labor. Of course, as other studies on vulnerable communities at Ball State, Brookings, academic papers, and a book on the subject, have said this is largely a function of educational attainment. I’ll return to this later.

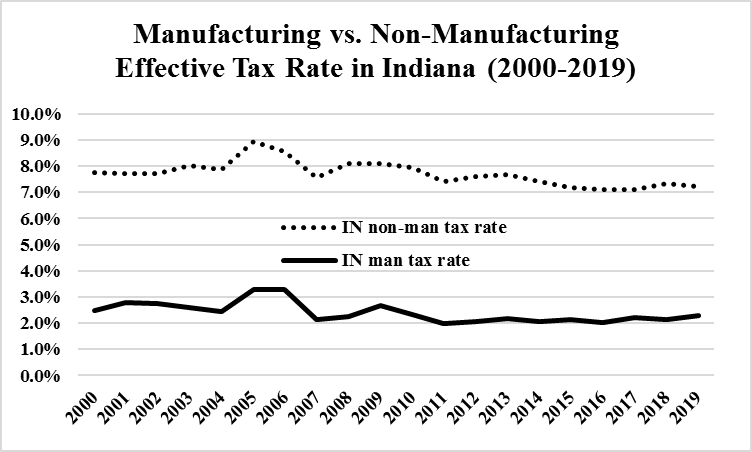

Indiana has hugely incentivized factories in the state, dropping our tax rate from 25th to 4th over 20 years.

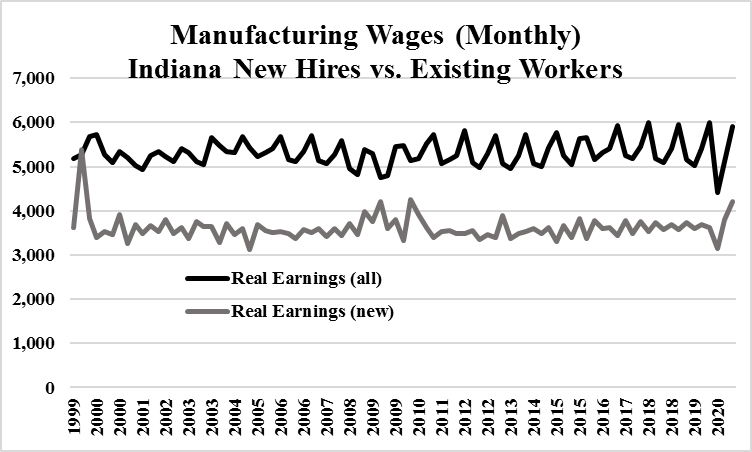

This of course hasn’t arrested job losses, nor has boosted wages for Hoosier workers. A factory job today pays no differently in Indiana than it did in the Clinton Administration, and a new factory job pays a bit less.

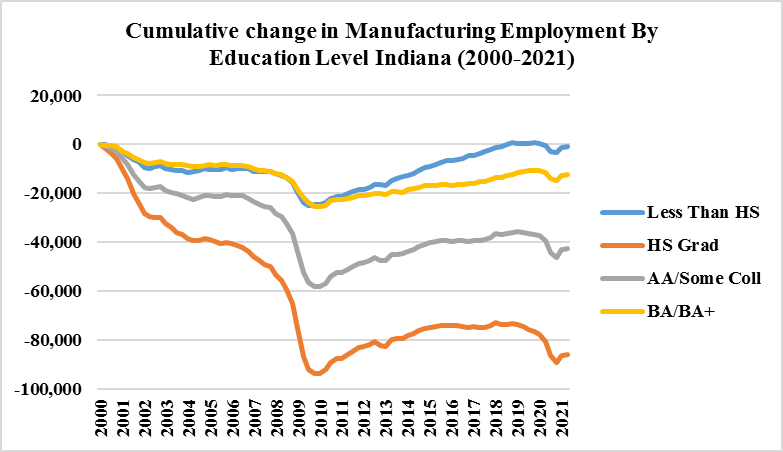

This is likely due to the changing composition of the labor force. Indiana has been a hot bed for low wage, low skilled (or at least low formal education) factory jobs. This graphic depicts cumulative employment growth in manufacturing in Indiana so far this century. The net job growth is wholly among those with less than a high school education (thee are QWI data for workers aged 25 and older).

This is a good time to restate the point that two decades of courting factory jobs has not caused job growth, has not increased the skill of factory workers or their wages, nor has it lessened volatility (as the wage graph shows above).

If evidence matters in the development of public policy, this is as damning a bit of evidence towards the status quo that I’ve seen.

I pick on Indiana because that is the charge of a state university professor. But, this problem extends far beyond Indiana. The problem is that most other states have also done something about the real problem that reduces wages and employment — which I’ll get to shortly.

While Indiana has been busy with tax cuts on factories, we’ve kept taxes high on non-manufacturing firms. You know these, they are the ones actually creating jobs in Indiana.

At the same time, there’s been a tremendous shift in the underlying fundamentals that generate income growth. Here in Indiana, business operating surplus is growing rapidly, while the labor share of production remains historically low.

This means that workers experience a declining share of GDP in terms of wages and benefits.

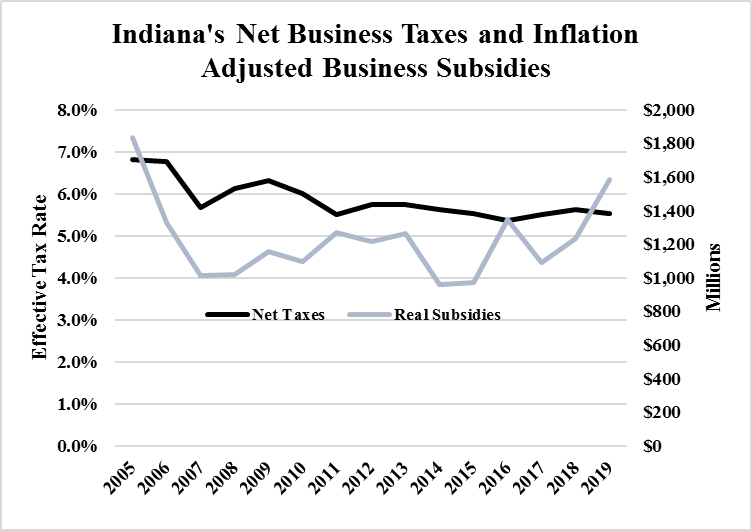

At the same time workers have seen declining or static incomes, government has cut taxes and increased subsidies to business. From 2014 to 2019, subsidies grew from $1 Billion to $1.6 Billion in real (inflation adjusted) terms. In 2019, each Hoosier family was paying roughly $560 annual subsidies to business.

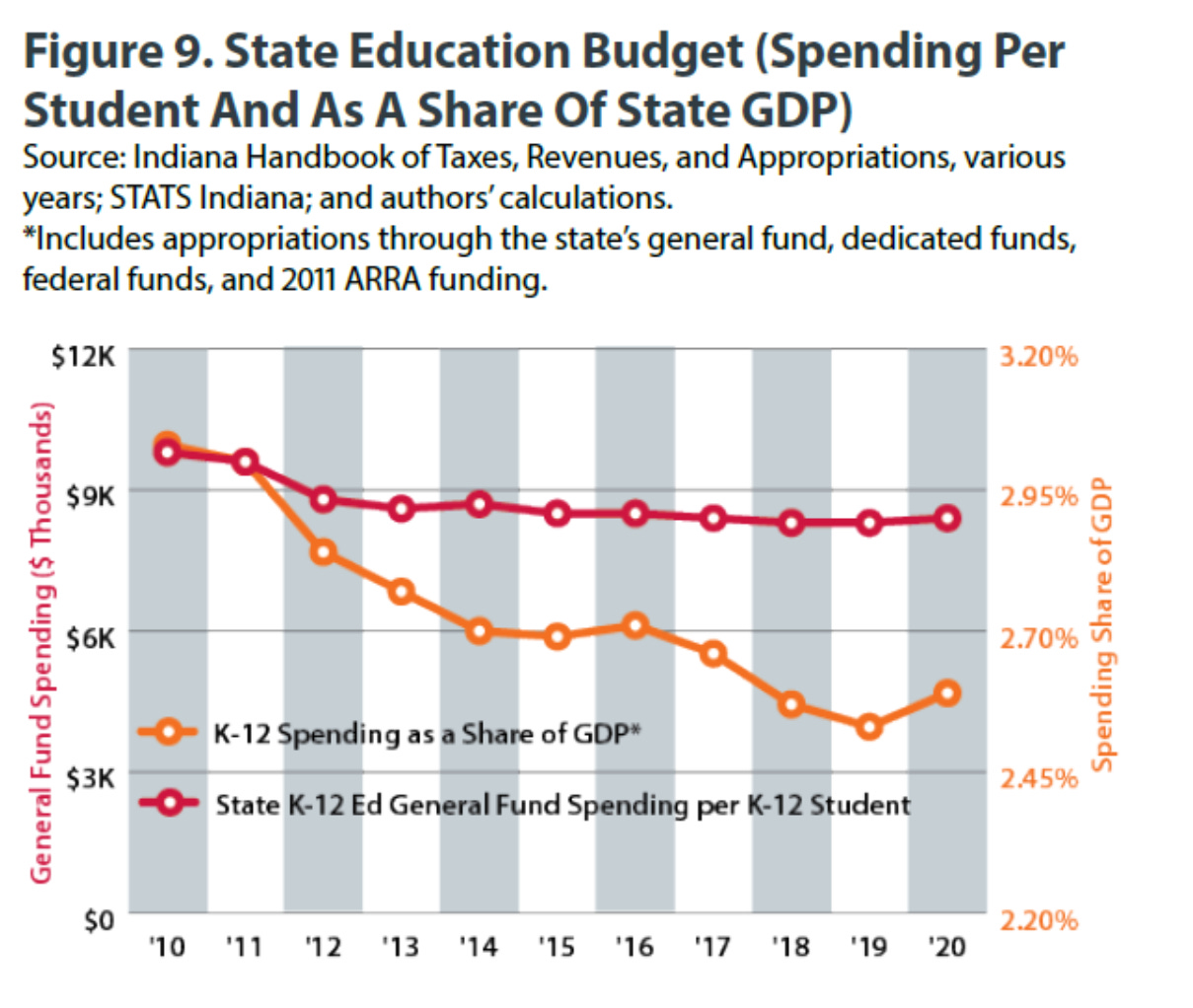

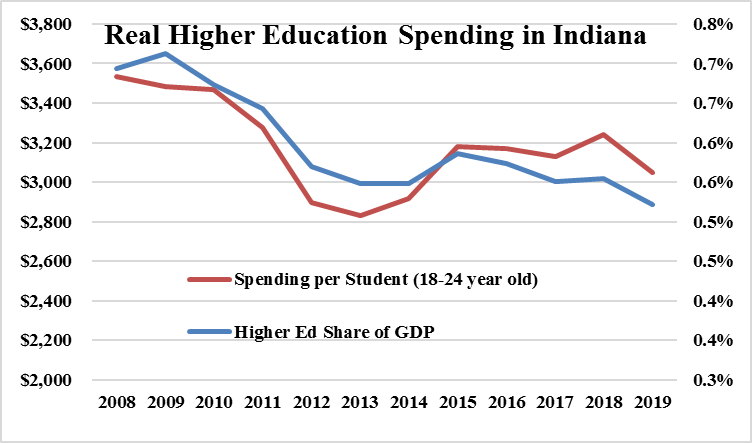

The benefits to Hoosiers from this combination of tax and spending cuts is difficult to see. Spending on public education is well down from 2010 levels, spending on higher education much lower than in 2010, and on a per student basis declining faster than at any time in state history.

Indiana is cutting taxes vigorously . . . which is clearly showing up in the profitability of Hoosier firms.

To be clear, profitable firms are good, a vibrant private sector necessary for a healthy democracy. But, as these tax cuts reduce government services, they have not translated into higher incomes for Hoosiers. We’ve gone from well above, to well below the national average in labor share of GDP in 20 years. (all data on these graphics from the National Income Accounts, reported by the BEA).

The state’s senior elected leaders like to tout Indiana’s great economic performance. But, it is a mirage. Over the past two decades, Indiana has outperformed the nation as a whole in fewer than six years. We are diverging away from the national average, not converging towards it.

I’d encourage anyone in the media to go back to the State of the State address and check the data Governor Holcomb shared. It ranges from purposefully distortionary, to flat out untrue. I am certain Governor Holcomb doesn’t gather his own statistics for these speeches, so I am not suggesting he is purposefully being untruthful.

However, he is responsible for the quality of his adminstrations’s staff work. And in that state of the state address, it was unacceptably poor.

Finally, I believe there’s a direct connection between unwise investments in public dollars and the poor economic performance of Indiana’s economy. As I said in this Marketwatch column, Indiana just doesn’t have the educated workforce the modern economy needs.

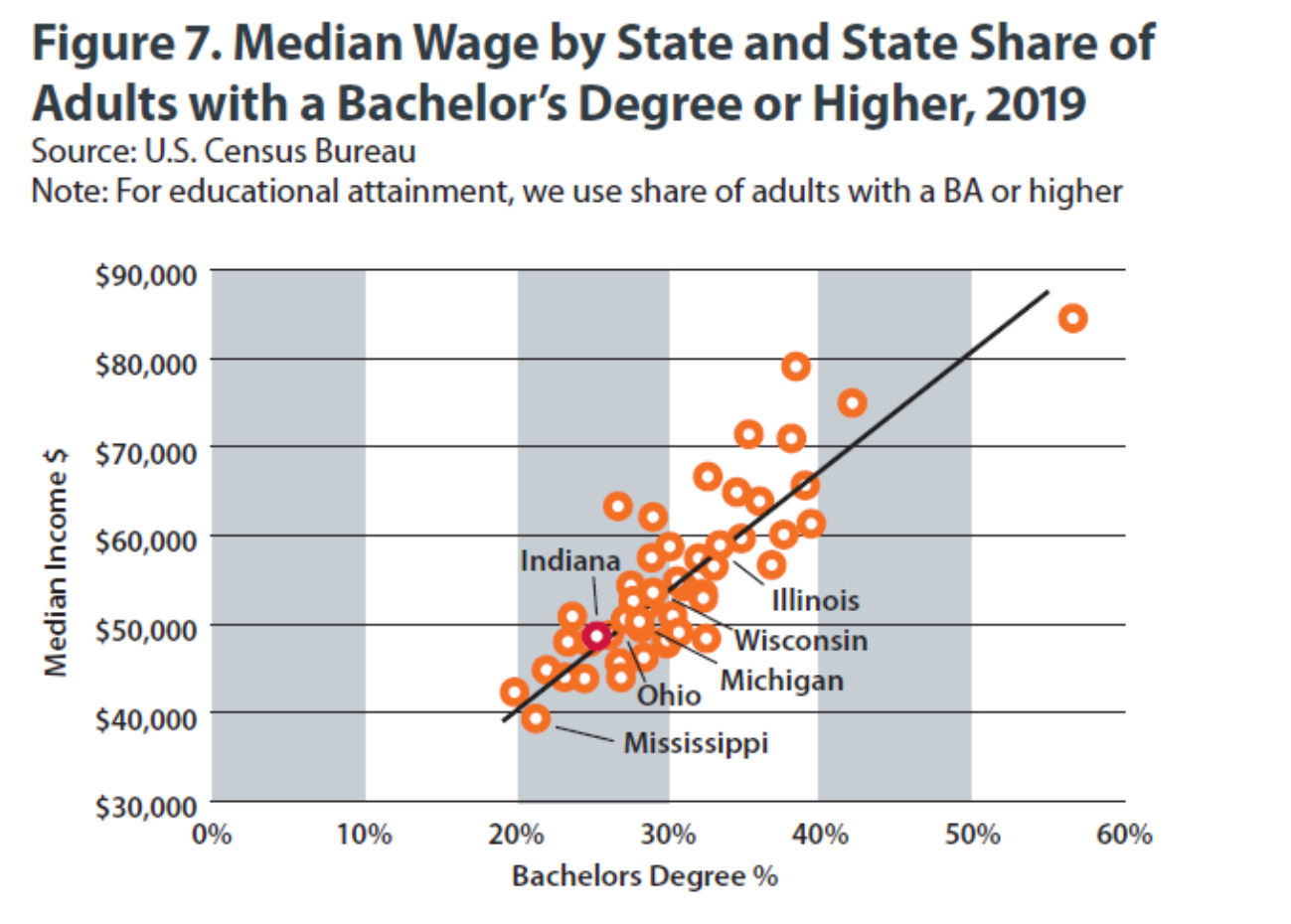

Educational attainment means higher wages for everyone. This graphic is from an as-yet unpublished study. Just so readers understand, the link between educational attainment and per capita income is not a mirage conjured by some faculty member. Rather it is one of the most continually regular empirical facts in the social sciences.

Indiana is losing educated workers at a record rate. In fact, the last decade (2010-2019) was the worst on record. Again, this graphic is from that forthcoming study.

There’s a lot going on here, but suffice it to say that Indiana has two problems: Educating enough people well, and causing educated workers to stay in the state. This involves both better focus on college enrollment, which has been in a deep slump since the mid 2010’s and giving local communities the capacity to remake themselves into places people wish to live.

Money matters, but this quest means greater local flexibility as well as greater focus on preparation and attendance at post-secondary education.

Our spending on K-12 lags, which then spills over into post secondary attendance. Post secondary spending declines, which helps reinforce the declining ‘go to college’ rate as well as the numbers of prepared graduates. Data for these graphs are from Census and the Nat’l Association of State Budget Officers.

The point I make here is that the pursuit of manufacturing employment is a hollow policy choice for Indiana taxpayers — except for the manufacturing firms that will see higher profitability, and more available capital for expansion. That expansion is unlikely to happen in Indiana, such as with the new Lilly manufacturing plant locating in North Carolina.

Indiana just doesn’t have the skilled and educated workforce for large advanced manufacturing firms, or the communities that would attract such workers. This is not an accident, it is the result of extensive policy choices. There’s a better way, as this Brookings study suggests.

Indiana policymakers need to have a deep and lengthy conversation about evidence based policy. Even then, it seems highly unlikely that Indiana will enjoy a better economy over the next decade than we did in the past. The past decade was very disappointing, and should be an alarm bell to every Hoosier policymaker.

(Note: This post has been updated to correct two typographic errors and include a note following the third paragraph).

What a powerful and understandable critique of how and why our economic development policies are letting us down. Bottom line, if we're unwilling to invest in our people and communities, private businesses will not invest in our state. Great job Professor.